For 20 years, astronauts have been shooting photos of Earth from the space station. Like everything the astronauts do, they are trained for this job. And like everything they do, there is purpose and intention behind it.

Learn more about astronaut photography and the ESRS team in parts 2 & 3 in the series:

Video Transcript:

For nearly 60 years, astronauts have been looking down at Earth from space. And all along, they have been shooting photos.

They have been doing so almost daily since November 2000, when the International Space Station became a permanent home to astronauts.

We’re over 3 million images in the archive. It is perhaps the longest continuous remote sensing record that we have for the Earth’s surface.

Like everything the astronauts do, they are trained for this job — to look at our planet and chronicle what they see. They don’t look at Earth and take photos just for the novelty, though there is definitely beauty, joy, and inspiration in it.

So it’s not just for fun and make them feel comfortable. There’s real use to it.

Space can be disorienting. So the astronauts are trained to orient themselves to their planet as they float above it.

In their first days in orbit, very little of what they see looks familiar. Knowing how to look at Earth can help them connect to home.

Most people don’t have a mental geography of any other place. I think it makes the world more manageable mentally so that they don’t feel as though it’s just overwhelmingly big.

Crews really like looking at the Earth. There have been studies done in the past that it provides an actual psychological benefit for them, to be tied back to their home planet.

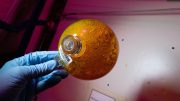

An astronaut with a camera is also useful to science and society. He or she can pick out features of Earth or observe natural events and snap images that have real societal value.

If the astronaut has any training at all, they recognize things that are out of the ordinary, and then they shoot it.

Some events are caught by chance. Others are shot at the request of federal and international agencies.

Folks on the ground would help me, when they knew, for example, weather or other events were taking place in the world,

they would help me by giving me those targets. Say there’s a storm here, or there’s a fire there, or there’s a volcano eruption over here.

In August 2017, Tropical Storm Harvey rapidly intensified into a category four hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. It sat for days off the coast of Texas and dumped record amounts of rain, leading to devastating floods.

With hurricane Harvey, we were able to document just the huge amounts of sediment outflow that came from that storm. Once the imagery is geo-referenced, then you can actually do measurements of what the extent of that sediment plume is.

We try to impress upon that on the crews during their training too, that we’re not just asking you to take pictures. This is actual science data that people are looking for, and we’re supporting external science requests to get this data. It’s a fundamentally different dataset than most polar orbiting satellites collect.

An astronaut can view a place from different angles, different fields of view, different times of day, and different lighting conditions. They make real-time decisions about the best way to view events and places on Earth.

The astronaut is doing the choosing ahead of the taking of the data, which is the exact opposite of what the satellites do. So you don’t need to take nearly so many. You take a fraction of 1% of the images and you still see very interesting stuff.

Of particular interest to scientists is how Earth changes over time.

Since we’ve got over 50 years of manned space flight photography of Earth, you can look at certain areas and get a timeline of what’s changed over time, like glaciers receding or growing.

Or this is Lake Eyre and I’ve never seen it with water before. Here it’s got water in it, bang, take the shot.

The photos also spur new discoveries. Scientists have used astronaut photographs to better understand lightning and auroras. They have observed unusual atmospheric phenomena like sprites and polar mesospheric clouds. They have studied how city lights affect animal behavior. And they have discovered inland deltas and river deposits called megafans.

Even in 1988, we thought we knew the dry surfaces of the planet. We didn’t, at a mesoscale, at that that middling scale. This photography specifically gave me a worldview which I hadn’t had before. And that was key to seeing that there are megafans around the planet.

Beyond their value to science, the photos shot by astronauts remind us of the beauty and wonder of our planet.

It’s really a bottomless vault of riches that anybody now in the world can go and search through that vault and tap into those riches and do so much with it.

There is also a somewhat more aesthetic component. Astronaut photographs of the Earth, they can look almost identical to an image you might take out of an airplane. Because of that, the data is immediately accessible to people.

Astronaut photography is unique in that it’s not just like a nadir-looking satellite image. It is a photo that someone picked up a camera and chose to take. Having that perspective of looking at Earth’s horizon and seeing these really wide landscapes where you can literally view different climate zones all within a photo, I think puts into perspective how connected our world is.

I think through capturing the imagery of all the different things on the surface of the Earth, all the phenomena that you can see from the vantage point. I think it just grew over time my appreciation for the uniqueness of Earth, for the resources that we find here, for what we’ve been able to do.

It elevates a sense of responsibility to steward those things, to care about them a little bit more, to appreciate them.

Be the first to comment on "NASA Picturing Earth: Astronaut Photography In Focus [Video]"