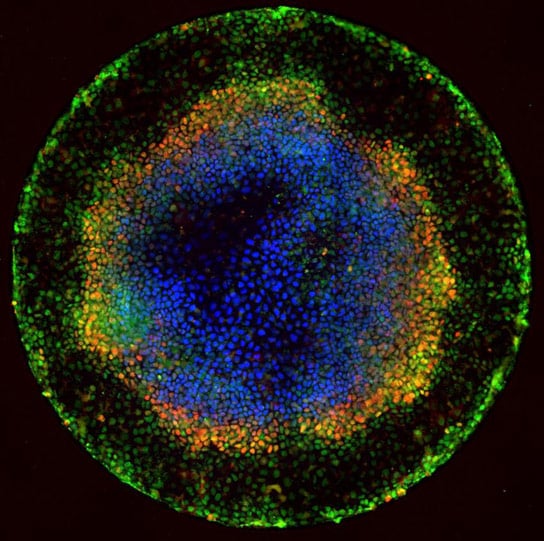

Forty-two hours after they began to differentiate, embryonic cells are clearly segregating into endoderm (red), mesoderm (blue), and ectoderm (black). Researchers say the key to achieving this patterning in culture is confining the colonies geometrically. Credit: Rockefeller University

Using geometry, scientists from the Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology and Molecular Embryology at Rockefeller University have coaxed human embryonic stem cells to organize themselves.

About seven days after conception, something remarkable occurs in the clump of cells that will eventually become a new human being. They start to specialize. They take on characteristics that begin to hint at their ultimate fate as part of the skin, brain, muscle, or any of the roughly 200 cell types that exist in people, and they start to form distinct layers.

Although scientists have studied this process in animals, and have tried to coax human embryonic stem cells into taking shape by flooding them with chemical signals, until now the process has not been successfully replicated in the lab. But researchers led by Ali Brivanlou, Robert and Harriet Heilbrunn Professor and head of the Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology and Molecular Embryology at The Rockefeller University, have done it, and it turns out that the missing ingredient is geometrical, not chemical.

“Understanding what happens in this moment, when individual members of this mass of embryonic stem cells begin to specialize for the very first time and organize themselves into layers, will be a key to harnessing the promise of regenerative medicine,” Brivanlou says. “It brings us closer to the possibility of replacement organs grown in petri dishes and wounds that can be swiftly healed.”

In the uterus, human embryonic stem cells receive chemical cues from the surrounding tissue that signal them to begin forming layers — a process called gastrulation. Cells in the center begin to form ectoderm, the brain, and skin of the embryo, while those migrating to the outside become mesoderm and endoderm, destined to become muscle, blood, and many of the major organs, respectively.

Brivanlou and his colleagues, including postdocs Aryeh Warmflash and Benoit Sorre as well as Eric Siggia, Viola Ward Brinning, and Elbert Calhoun Brinning Professor and head of the Laboratory of Theoretical Condensed Matter Physics, confined human embryonic stem cells originally derived at Rockefeller to tiny circular patterns on glass plates that had been chemically treated to form “micropatterns” that prevent the colonies from expanding outside a specific radius. When the researchers introduced chemical signals spurring the cells to begin gastrulation, they found the colonies that were geometrically confined in this way proceeded to form endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm and began to organize themselves just as they would have under natural conditions. Cells that were not confined did not.

By monitoring specific molecular pathways the human cells use to communicate with one another to form patterns during gastrulation — something that was not previously possible because of the lack of a suitable laboratory model — the researchers also learned how specific inhibitory signals generated in response to the initial chemical cues function to prevent the cells within a colony from all following the same developmental path.

The research was published June 29 in Nature Methods.

“At the fundamental level, what we have developed is a new model to explore how human embryonic stem cells first differentiate into separate populations with a very reproducible spatial order just as in an embryo,” says Warmflash. “We can now follow individual cells in real time in order to find out what makes them specialize, and we can begin to ask questions about the underlying genetics of this process.”

The research also has direct implications for biologists working to create “pure” populations of specific cells, or engineered tissues consisting of multiple cell types, for use in medical treatments. “These cells have a powerful intrinsic tendency to form patterns as they develop,” Warmflash says. “Varying the geometry of the colonies may turn out to be an important tool that can be used to guide stem cells to form specific cell types or tissues.”

Reference: “A method to recapitulate early embryonic spatial patterning in human embryonic stem cells” by Aryeh Warmflash, Benoit Sorre, Fred Etoc, Eric D Siggia and Ali H Brivanlou, 29 June 2014, Nature Methods.

DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.3016

Be the first to comment on "Scientists Coax Human Embryonic Stem Cells to Organize"