Scientists have been warning about an ‘insect apocalypse’ in recent years, noting sharp declines in specific areas — particularly in Europe. A new study shows these warnings may have been exaggerated and are not representative of what’s happening to insects on a larger scale. Credit: UGA

Long-term ecological site study shows no net insect changes.

Scientists have been warning about an “insect apocalypse” in recent years, noting sharp declines in specific areas — particularly in Europe. A new study shows these warnings may have been exaggerated and are not representative of what’s happening to insects on a larger scale.

University of Georgia professor of agroecology Bill Snyder sought to find out if the so-called “insect apocalypse” is really going to happen, and if so, had it already begun. Some scientists say it might be only 30 years before all insects are extinct, so this is a really important and timely question for agriculture and conservation.

Snyder and a team of researchers from UGA, Hendrix College, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture used more than 5,300 data points for insects and other arthropods — collected over four to 36 years at monitoring sites representing 68 natural and managed areas — to search for evidence of declines across the United States.

Some groups and sites showed increases or decreases in abundance and diversity, but many remained unchanged, yielding net abundance and biodiversity trends generally indistinguishable from zero. This lack of overall increase or decline was consistent across arthropod feeding groups, and was similar for heavily disturbed versus relatively natural sites. These results were recently published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Local observations

The idea for the study started last year with a cross-country road trip for Snyder from Washington state to his new home in Georgia.

“I had the same observation a lot of people had. We had our drive across the country — you don’t see as many insects squished on your car or windshield.”

When he got to his home in Bishop, Georgia, it seemed like a different story.

“I noticed the lights outside were full of insects, as many as I remember as a kid,” he said. “People have this notion — there seems like [there are] fewer insects — but what is the evidence?”

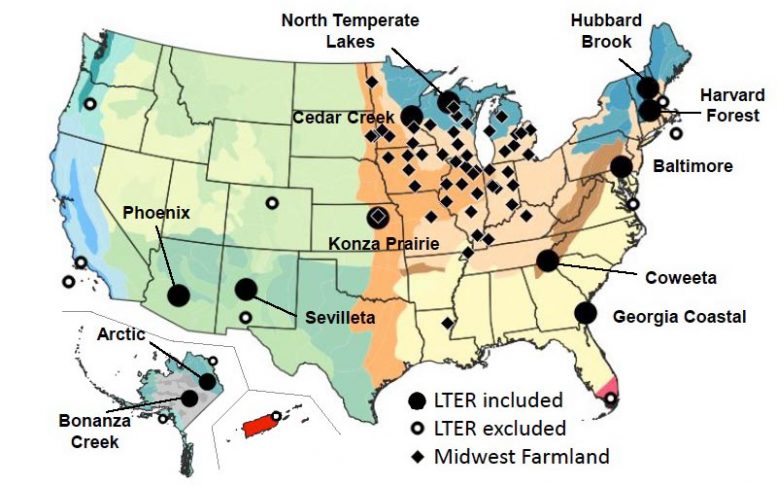

Filled black circles represent LTER sites with arthropod data that were included in the study. Colors on the underlying map delineate ecoregions as defined by the USDA Forest Service.

There is some alarming evidence that European honey bees have problems, but Snyder was curious if insects everywhere are in decline. “We depend on insects for so many things,” he said. “If insects disappear it would be really, really bad. Maybe the end of human existence.”

He was discussing the topic with another biologist and friend, Matthew Moran at Hendrix College, and they recalled the U.S. National Science Foundation’s network of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites, which were established in 1980 and encompass a network of 25 monitoring locations across each of the country’s major ecoregions.

Ecological sampling

The NSF’s LTER data is publicly available, but has not previously been gathered into a single dataset to be examined for evidence of broad-scale density and biodiversity change through time until now.

Arthropod data sampled by the team included grasshoppers in the Konza Prairie in Kansas; ground arthropods in the Sevilleta desert/grassland in New Mexico; mosquito larvae in Baltimore, Maryland; macroinvertebrates and crayfish in North Temperate Lakes in Wisconsin; aphids in the Midwestern U.S.; crab burrows in Georgia coastal ecosystems; ticks in Harvard Forest in Massachusetts; caterpillars in Hubbard Brook in New Hampshire; arthropods in Phoenix, Arizona; and stream insects in the Arctic in Alaska.

The team compared the samples with human footprint index data, which includes multiple factors like insecticides, light pollution and built environments to see if there were any overall trends.

“No matter what factor we looked at, nothing could explain the trends in a satisfactory way,” said Michael Crossley, a postdoctoral researcher in the UGA department of entomology and lead author of the study. “We just took all the data and, when you look, there are as many things going up as going down. Even when we broke it out in functional groups there wasn’t really a clear story like predators are decreasing or herbivores are increasing.”

“This is an implication for conservation and one for scientists, who have been calling for more data due to under-sampling in certain areas or certain insects. We took this opportunity to use this wealth of data that hasn’t been used yet,” explained Crossley, an agricultural entomologist who uses molecular and geospatial tools to understand pest ecology and evolution and to improve management outcomes. “There’s got to be even more data sets that we don’t even know about. We want to continue to canvass to get a better idea about what’s going on.”

Good and bad news

To answer Snyder’s broad question of, “Are there overall declines?” No, according to the study. “But we’re not going to ignore small changes,” Snyder said. “It’s worthwhile to differentiate between the two issues.”

Particular insect species that we rely on for the key ecosystem services of pollination, natural pest control, and decomposition remain unambiguously in decline in North America, the authors note.

In Europe, where studies have found dramatic insect declines, there may be a bigger, longer-term impact on insects than the U.S., which has a lower population density, according to Snyder.

“It’s not the worst thing in the world to take a deep breath,” suggested Snyder. “There’s been a lot of environmental policies and changes. A lot of the insecticides used in agriculture now are narrow-acting. Some of those effects look like they may be working.”

When it comes to conservation, there’s always room for everyone to pitch in and do their part.

“It’s hard to tell when you’re a single homeowner if you’re having an effect when you plant more flowers in your garden,” he said. “Maybe some of these things we’re doing are starting to have a beneficial impact. This could be a bit of a hopeful message that things that people are doing to protect bees, butterflies, and other insects are actually working.”

Reference: “No net insect abundance and diversity declines across US Long Term Ecological Research sites” by Michael S. Crossley, Amanda R. Meier, Emily M. Baldwin, Lauren L. Berry, Leah C. Crenshaw, Glen L. Hartman, Doris Lagos-Kutz, David H. Nichols, Krishna Patel, Sofia Varriano, William E. Snyder and Matthew D. Moran, 10 August 2020, Nature Ecology & Evolution.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-020-1269-4

I don’t need a scientist title to rebut this article. The truth is that some 20 – 25 years back my car windshield needed a maximal insect cleaning after few hundred kilometers drive in summer. Those days is absolutely clean, maybe some 2-3 sticking insects on it.

I think the cars of today are rigorously tested in wind tunnels to get the mpg as good as possible. The motorbike and I get splattered with insects on the commute. The car, when I have to drop the kids to school (I drive a large estate), remains surprisingly insect free. Maybe I drive slower in the car so the insects can move out the way? The only true conclusion you can make is that a windscreen is a very poor way to count insect populations…

As a naturalist for 60 years, the decline in insects is staggering. These are my personal observations. This article refuted itself with two sentences, and it’s only looking at the past for 4-36 years. I know for a fact there are a whole lot less insects now than there were fifty or sixty years ago. You don’t even get them splattered on your window at all anymore.

Maybe cars are doing alot to wipe them out …

The title of the study says ‘ No net insect abundance and diversity declines across US Long Term Ecological Research sites’

Yet this paragraph…

‘Particular insect species that we rely on for the key ecosystem services of pollination, natural pest control and decomposition remain unambiguously in decline in North America, the authors note.’

That strikes me as ambiguous if not disingenuous. Also, I’m not sure the time frame is long enough. A start point that pre-dated agricultural crop spraying would, I think give a more accurate report of insect populations.

I live in the suburban Detroit area of Michigan. This year, for the first time that I can remember, we’re actually seeing more butterflies than normal. Wasps and hornets seem normal. Bees, very rarely. Also grasshoppers, which you used to see in fields everywhere all the time, very rare.

We used to have a large dairy for our area in South West Missouri.put up several hundred acres of corn silage the year after triple stacked corn came out I could see a notable decrease I flys. Don’t remember exactly what year that was. But it was obvious which everyone welcomed thought then. Maybe part of the problem today. Everyone said I was crazy.

…..that’s your measure? Bugs on your windshield? You do realize they manufacture them to purposely avoid getting bug splatters, right? Vehicles are designed specifically to reduce splatter, and you’re using that to measure? Not to mention the fact that when I drive long distances, late 90’s vehicle is absolutely riddled with bugs.