Sea ice floes gather in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica. A new research review integrates decades of satellite measurements to reveal how and why Antarctica’s glaciers, ice shelves and sea ice are changing. Sinéad Farrell

New research review provides insights into the continent’s response to climate warming.

Scientists from the University of Maryland, the University of Leeds, and the University of California, San Diego, have reviewed decades of satellite measurements to reveal how and why Antarctica’s glaciers, ice shelves, and sea ice are changing.

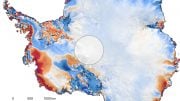

Their report, published in a special Antarctica-focused issue of the journal Nature on June 14, 2018, explains how ice shelf thinning and collapse have triggered an increase in the continent’s contribution to sea level rise. The researchers also found that, although the total area of sea ice surrounding Antarctica has shown little overall change since the advent of satellite observations, mid-20th century ship-based observations suggest a longer-term decline.

“Antarctica is way too big to survey from the ground, and we can only truly understand the trends in its ice cover by looking at the continent from space,” said Andrew Shepherd, a professor of Earth observation at the University of Leeds’ School of Earth and Environment and the lead author of the review.

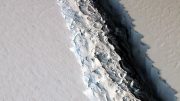

In West Antarctica, ice shelves are being eaten away by warm ocean water, and those in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen seas have thinned by as much as 18 percent since the early 1990s. At the Antarctic Peninsula, where air temperatures have risen sharply, ice shelves have collapsed as their surfaces have melted. Altogether, 34,000 square kilometers (more than 13,000 square miles) of ice shelf area has been lost since the 1950s.

More than 150 studies have tried to determine how much ice the continent is losing. The biggest changes have occurred in places where ice shelves–the continent’s protective barrier–have either thinned or collapsed.

“Although breakup of the ice shelves does not contribute directly to sea-level rise–since ice shelves, like sea ice, are already floating–we now know that these breakups have implications for the inland ice,” said Helen Fricker, a professor of glaciology at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego and a co-author of the review. “Without the ice shelf to act as a natural buffer, glaciers can flow faster downstream and out to sea.”

In the Amundsen Sea, for example, ice shelf thinning of up to 6 meters (nearly 20 feet) per year has accelerated the advance of the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers by as much as 1.5 kilometers (nearly 1 mile) per year. These glaciers have the potential to raise sea levels by more than a meter (more than three feet) and are now widely considered to be unstable.

Meanwhile, satellite observations have provided an increasingly detailed picture of sea ice cover, allowing researchers to map the extent, age, motion, and thickness of the ice. The combined effects of climate variability, atmosphere and ocean circulation, and even ice shelf melting have driven regional changes, including reductions in sea ice in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen seas.

“The waxing and waning of the sea ice controls how much sunlight is reflected back to space, cooling the planet,” said Sinéad Farrell, an associate research scientist at UMD’s Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center and a co-author of the review. “Regional sea ice loss impacts the temperature and circulation of the ocean, as well as marine productivity.”

Other findings covered by the research review include:

- The Antarctic continent is covered by about 15.5 million square kilometers (nearly 6 million square miles) of ice, which has accumulated over thousands of years through snowfall. The weight of new snow compresses the older snow below it to form solid ice.

- Glaciers flowing down the ice sheet spread under their own weight as they flow toward the ocean and eventually lose contact with the bedrock, forming about 300 floating ice shelves that fringe the continent. These shelves contain about 10 percent–or 1.5 million square kilometers (nearly 600,000 square miles)–of Antarctica’s ice.

- In the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, sea ice expands and contracts as ocean water freezes and melts throughout the year. The sea ice covers an area of 18.5 million square kilometers (more than 7 million square miles) in winter and grows to about 1 meter (more than 3 feet) thick.

- It is estimated that there is enough water locked up in Antarctica’s ice sheet to raise global sea levels by more than 50 meters (more than 164 feet).

New and improved satellite missions, such as Sentinel-3, the recently launched Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment Follow-On (GRACE-FO), and the eagerly awaited ICESat-2, will continue to give researchers more detailed insights into the disappearance of Antarctic ice.

Reference: “Trends and connections across the Antarctic cryosphere” by Andrew Shepherd, Helen Amanda Fricker and Sinead Louise Farrell , 13 June 2018, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0171-6

Be the first to comment on "Scientists Reveal How And Why Antarctica’s Glaciers Are Changing"