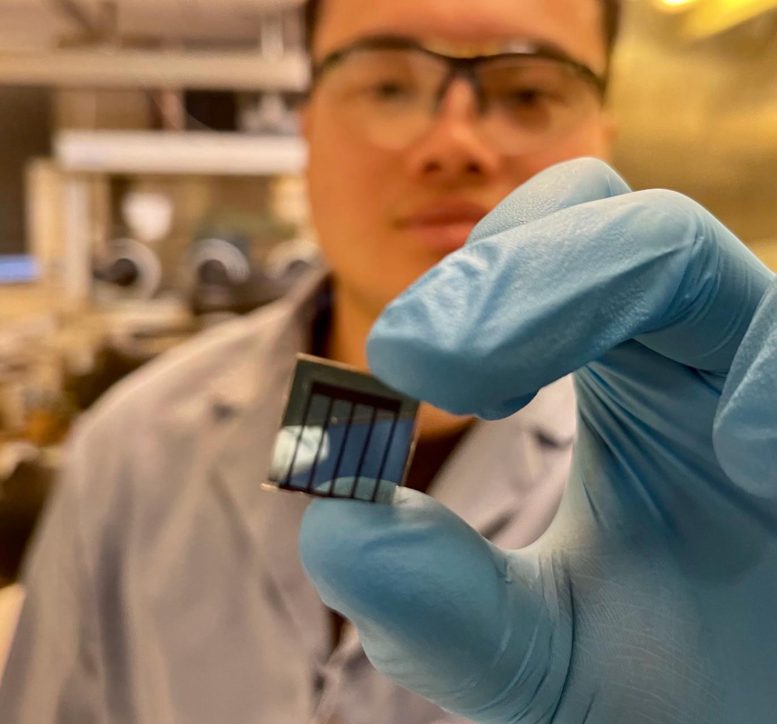

An international team led by UCLA researchers has developed a way to use perovskite in solar cells while protecting it from the conditions that cause it to deteriorate. Credit: Yang Lab/UCLA

Using enhanced halide perovskite in place of silicon could produce less expensive devices that stand up better to light, heat.

Amid all of the efforts to convert the nation’s energy supply to renewable sources, solar power still accounts for a little less than 3% of electricity generated in the U.S. In part, that’s because of the relatively high cost to produce solar cells.

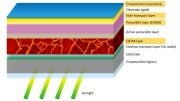

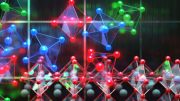

One way to lower the cost of production would be to develop solar cells that use less-expensive materials than today’s silicon-based models. To achieve that, some engineers have zeroed in on halide perovskite, a type of human-made material with repeating crystals shaped like cubes.

In theory, perovskite-based solar cells could be made with raw materials that cost less and are more readily available than silicon; they also could be produced using less energy and a simpler manufacturing process.

But so far, a stumbling block has been that perovskite breaks down with exposure to light and heat — particularly problematic for devices meant to generate energy from the sun.

Yepin Zhao, a UCLA postdoctoral researcher and first author of the study, holds a perovskite-based solar cell. Credit: Yang Lab/UCLA

Now, an international research collaboration led by UCLA has developed a way to use perovskite in solar cells while protecting it from the conditions that cause it to deteriorate. In a study that was published recently in Nature Materials, the scientists added small quantities of ions — electrically charged atoms — of a metal called neodymium directly to perovskite.

They found not only that the augmented perovskite was much more durable when exposed to light and heat, but also that it converted light to electricity more efficiently.

“Renewable energy is critically important,” said corresponding author Yang Yang, the Carol and Lawrence E. Tannas, Jr. Professor of Engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering and a member of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. “Perovskite will be a game changer because it can be mass produced in a way silicon cannot, and we’ve identified an additive that will make the material better.”

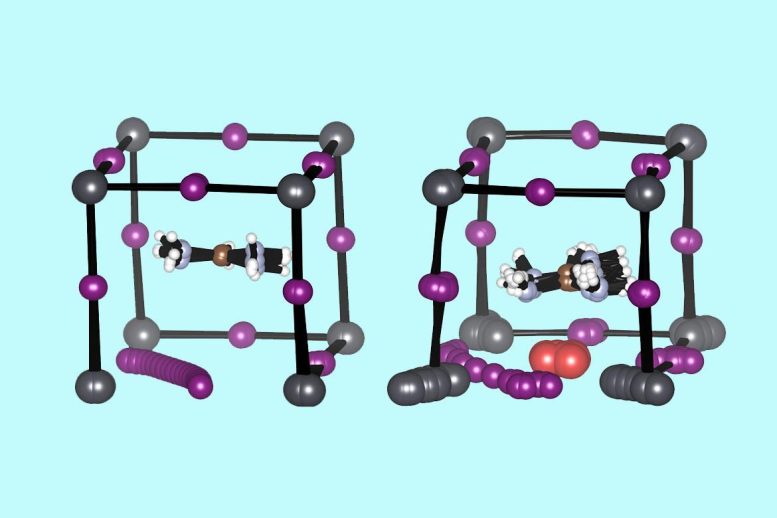

Halide perovskite’s ability to convert light to electricity is due to the way its molecules form a repeating grid of cubes. That structure is held together by bonds between ions with opposite charges. But light and heat tend to cause negatively charged ions to pop out of the perovskite, which damages the crystal structure and diminishes the material’s energy-converting properties.

Diagrams showing the structure of an unaltered perovskite molecule (left) with iodine ions (purple) migrating away; and a perovskite molecule with neodymium ions (red) added to help retain iodine ions. Credit: Yang Lab/UCLA

Neodymium is commonly used in microphones, speakers, lasers and decorative glass. Its ions are just the right size to nestle within a cubic perovskite crystal, and they carry three positive charges, which the scientists hypothesized would help hold negatively charged ions in place.

The researchers added about eight neodymium ions for every 10,000 molecules of perovskite and then tested the material’s performance in solar cells. Working at maximum power and exposed to continuous light for more than 1,000 hours, a solar cell using the augmented perovskite retained about 93% of its efficiency in converting light to electricity. In contrast, a solar cell using standard perovskite lost half of its power conversion efficiency after 300 hours under the same conditions.

The team also shined continuous light on solar cells without any equipment drawing power, which accelerates the degradation of perovskite. A device using perovskite with neodymium retained 84% of its power conversion efficiency after more than 2,000 hours, while a device with standard perovskite retained none of its efficiency after that amount of time.

To test the material’s ability to withstand high temperatures, the researchers heated solar cells with both materials to about 180 degrees Fahrenheit. The solar cell with augmented perovskite held onto about 86% of its efficiency after more than 2,000 hours, while a standard perovskite device completely lost its ability to convert light to electricity during that time.

In many previous studies aimed at making perovskite more durable, researchers have experimented with adding protective layers to the material, but that has largely failed. The idea to augment the material itself came from lead author Yepin Zhao, a postdoctoral researcher in Yang’s lab. Zhao said he was inspired by a technique commonly used in the production of silicon semiconductors — adding small amounts of other compounds to modify the material’s properties.

“The ions tend to move through the perovskite like cars on the highway, and that causes the material to break down,” Zhao said. “With neodymium, we identified a roadblock to slow down the traffic and protect the material.”

Yang said the advance could help perovskite solar cells reach the market within the next two to three years.

Reference: “Suppressing ion migration in metal halide perovskite via interstitial doping with a trace amount of multivalent cations” by Yepin Zhao, Ilhan Yavuz, Minhuan Wang, Marc H. Weber, Mingjie Xu, Joo-Hong Lee, Shaun Tan, Tianyi Huang, Dong Meng, Rui Wang, Jingjing Xue, Sung-Joon Lee, Sang-Hoon Bae, Anni Zhang, Seung-Gu Choi, Yanfeng Yin, Jin Liu, Tae-Hee Han, Yantao Shi, Hongru Ma, Wenxin Yang, Qiyu Xing, Yifan Zhou, Pengju Shi, Sisi Wang, Elizabeth Zhang, Jiming Bian, Xiaoqing Pan, Nam-Gyu Park, Jin-Wook Lee and Yang Yang, 17 November 2022, Nature Materials.

DOI: 10.1038/s41563-022-01390-3

Other UCLA authors of the study are Shaun Tan, Tianyi Huang, Rui Wang and Jingjing Xue, who earned doctorates; postdoctoral researchers Dong Meng and Tae-Hee Han; doctoral students Wenxin Yang and Qiyu Xing; Anni Zhang, who recently earned a master’s degree; and undergraduates Yifan Zhou and Elizabeth Zhang. Other co-authors are from Marmara University in Turkey, Sungkyunkwan University in Korea, Dalian University of Technology and Westlake University in China, Washington State University, UC Irvine and Washington University in St. Louis.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Korea’s National Research Foundation, China’s National Natural Science Foundation and Turkey’s Scientific and Technological Research Council.

“… led by UCLA has developed a way to use perovskite in solar cells …”

The statement is incorrect. Perovskite is a specific mineral with a unique chemical formula. What is being talked about is a synthetic (does not occur in nature) chemical with different elements than what occur in perovskite. It has a crystal structure similar to perovskite (isostructural). Sloppy use of terminology can lead to misunderstanding.

What should be said is “a material structurally similar to the mineral perovskite.” I suggest that it be given a new name such as “PVskite” or “Solarite” to avoid confusion. You wouldn’t call a Ford a Chevy just because they both have four wheels and an engine in the front.

Hey, Clyde… the material is identified and named as “halide perskovite” very clearly. It also very clearly states that it is a “…human-made material…”

After reading this information early in the article, one understands that for the remainder of the article, “perskovite” refers to “halide perskovite”, which is specifically what the whole article is about.