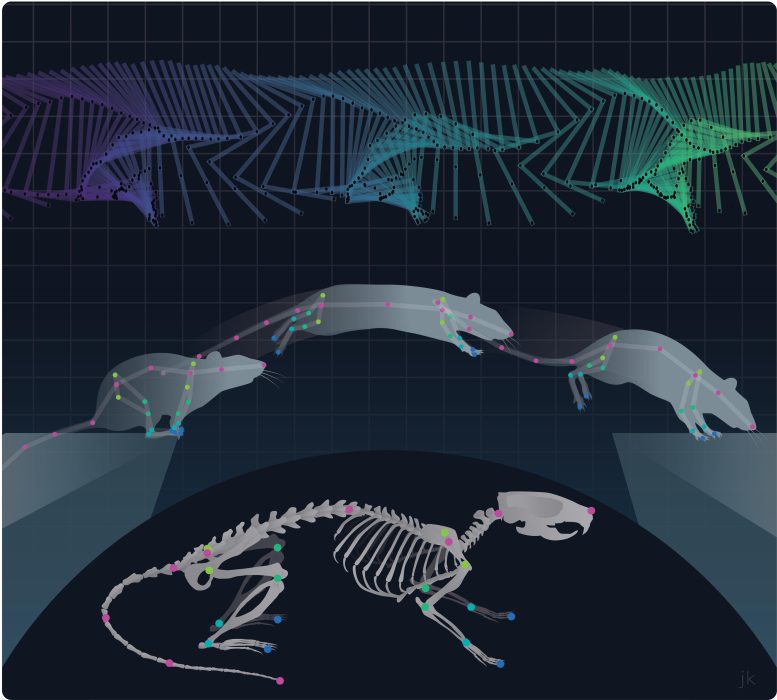

Model to estimate skeletal kinematics. Credit: Julia Kuhl

A new technique has been developed to track and measure the movement of skeletons in freely moving rodents.

How can researchers accurately and precisely measure the motion of a skeleton in a furry animal as it moves through its environment? The Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior – caesar has developed a new method that involves constructing a skeleton model which calculates bone joint movement using anatomical principles such as joint rotation limits and body movement speeds. This approach allows for a better understanding of how animals interact with their surroundings and can potentially reveal the connection between neuronal activity and complex behaviors such as decision-making, as the brain and spinal cord control movement.

Have you ever thought about the motion of your skeleton as you go about your daily activities? X-ray images may come to mind when we think about this question. But how can we measure the motion of a skeleton in a moving animal that interacts with its environment without using x-rays? And why is this important? Studying the freely moving animal can provide unique insights into how animals behave and make decisions, such as avoiding predators, finding mates, and raising their young.

While many studies have measured animal behavior, studies that measure the mechanics of how they move have been missing. But as activity in the central nervous system ultimately leads to decisions that are enacted through body movements, measuring these mechanics and relating them to neural activity is essential for gaining deep insights into brain function.

Credit: MPINB

Without an x-ray machine, analyzing movements of individual bones is extremely challenging as occluding overlaying fur, skin and soft tissue make it complicated to get a measurement of the skeleton’s motion. Recently, several advanced machine-learning methods have been able to accurately measure an animal’s pose and even changes in an animal’s facial expression; however, so far none of the existing techniques have been able to track the changes in bone positions and joint motion under visible body surface.

Researchers of the department Behavior and Brain Organization at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior in Bonn, headed by Jason Kerr, have now developed a videography-based method for 3D-tracking the skeleton at the resolution of single joints in untethered animals while they interact with their environment. Their Anatomically Constrained Model (ACM) is based on an anatomically grounded skeleton that infers the skeletal kinematics of an animal as it moves freely around.

From this data it was possible to measure the inner workings of a skeleton, moment to moment, as the animals jumped, walked, stretched and ran around. This new approach can be applied to multiple furry species such as mice and rats of different sizes and ages. To ensure that the data was right, the researchers worked with colleagues from the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tuebingen actually using MRI scanning of the animals to compare the ACM model to the actual skeleton.

“Our new method is relatively simple, tether-free and uses overhead cameras. It solves many problems associated with tracking freely moving rodents, especially those that are covered in fur and when the body covers the legs and feet” says Jason Kerr, who ran the study together with Jakob Macke from Tuebingen University.

One of the next steps is to combine this approach with simultaneous recordings from neurons in the brain using the miniature head-mounted multiphoton microscopes the researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology of Behavior have developed. This would allow to exactly correlate neural activity with actual behavior to find out more about how the brain controls even complex behavior.

The researchers will also apply their new method to measure motion kinematics in other animal species in more natural environments and simultaneously in multiple, interacting animals. “Using our new method, we will on one hand gain further insights on how animals interact with their environment and, on the other hand, we hope to gain knowledge of how animals interact with each other.” says Jason Kerr.

Reference: “Estimation of skeletal kinematics in freely moving rodents” by Arne Monsees, Kay-Michael Voit, Damian J. Wallace, Juergen Sawinski, Edyta Charyasz, Klaus Scheffler, Jakob H. Macke and Jason N. D. Kerr, 17 October 2022, Nature Methods.

DOI: 10.1038/s41592-022-01634-9

Be the first to comment on "Uncovering the Secrets of Skeleton Motion"