Complex disease transmission patterns could explain why it took tens of thousands of years after first contact for our ancestors to replace Neanderthals throughout Europe and Asia.

Growing up in Israel, Gili Greenbaum would give tours of local caves once inhabited by Neanderthals and wonder along with others why our distant cousins abruptly disappeared about 40,000 years ago. Now a scientist at Stanford, Greenbaum thinks he has an answer.

In a new study published in the journal Nature Communications, Greenbaum and his colleagues propose that complex disease transmission patterns can explain not only how modern humans were able to wipe out Neanderthals in Europe and Asia in just a few thousand years but also, perhaps more puzzling, why the end didn’t come sooner.

“Our research suggests that diseases may have played a more important role in the extinction of the Neanderthals than previously thought. They may even be the main reason why modern humans are now the only human group left on the planet,” said Greenbaum, who is the first author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher in Stanford’s Department of Biology.

The slow kill

Archeological evidence suggests that the initial encounter between Eurasian Neanderthals and an upstart new human species that recently strayed out of Africa — our ancestors — occurred more than 130,000 years ago in the Eastern Mediterranean in a region known as the Levant.

Yet tens of thousands of years would pass before Neanderthals began disappearing and modern humans expanded beyond the Levant. Why did it take so long?

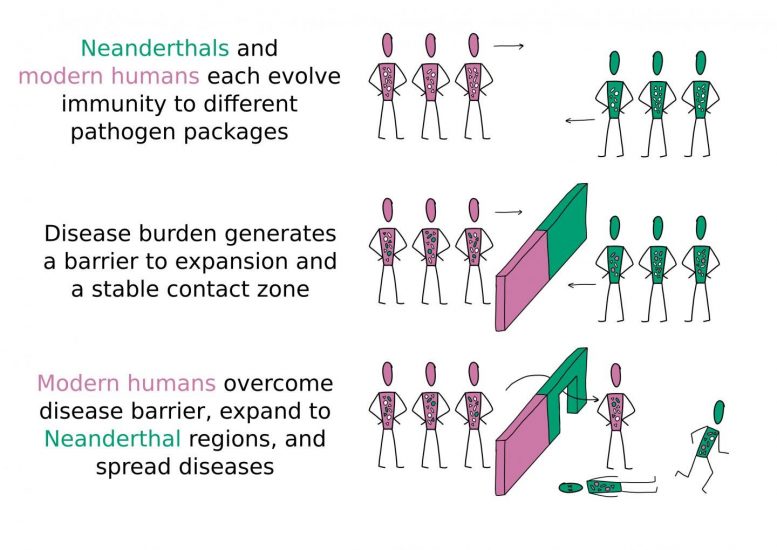

Employing mathematical models of disease transmission and gene flow, Greenbaum and an international team of collaborators demonstrated how the unique diseases harbored by Neanderthals and modern humans could have created an invisible disease barrier that discouraged forays into enemy territory. Within this narrow contact zone, which was centered in the Levant where first contact took place, Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted in an uneasy equilibrium that lasted tens of millennia.

This is an illustration of modern humans overcoming disease burden before Neanderthals. Credit: Vivian Chen Wong

Ironically, what may have broken the stalemate and ultimately allowed our ancestors to supplant Neanderthals was the coming together of our two species through interbreeding. The hybrid humans born of these unions may have carried immune-related genes from both species, which would have slowly spread through modern human and Neanderthal populations.

As these protective genes spread, the disease burden or consequences of infection within the two groups gradually lifted. Eventually, a tipping point was reached when modern humans acquired enough immunity that they could venture beyond the Levant and deeper into Neanderthal territory with few health consequences.

“Our research suggests that diseases may have played a more important role in the extinction of the Neanderthals than previously thought. They may even be the main reason why modern humans are now the only human group left on the planet.” — Gili Greenbaum

At this point, other advantages that modern humans may have had over Neanderthals — such as deadlier weapons or more sophisticated social structures — could have taken on greater importance. “Once a certain threshold is crossed, disease burden no longer plays a role, and other factors can kick in,” Greenbaum said.

Why us?

To understand why modern humans replaced Neanderthals and not the other way around, the researchers modeled what would happen if the suite of tropical diseases our ancestors harbored were deadlier or more numerous than those carried by Neanderthals.

“The hypothesis is that the disease burden of the tropics was larger than the disease burden in temperate regions. An asymmetry of disease burden in the contact zone might have favored modern humans, who arrived there from the tropics,” said study co-author Noah Rosenberg, the Stanford Professor of Population Genetics and Society in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

According to the models, even small differences in disease burden between the two groups at the outset would grow over time, eventually giving our ancestors the edge. “It could be that by the time modern humans were almost entirely released from the added burden of Neanderthal diseases, Neanderthals were still very much vulnerable to modern human diseases,” Greenbaum said. “Moreover, as modern humans expanded deeper into Eurasia, they would have encountered Neanderthal populations that did not receive any protective immune genes via hybridization.”

The researchers note that the scenario they are proposing is similar to what happened when Europeans arrived in the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries and decimated indigenous populations with their more potent diseases.

If this new theory about the Neanderthals’ demise is correct, then supporting evidence might be found in the archeological record. “We predict, for example, that Neanderthal and modern human population densities in the Levant during the time period when they coexisted will be lower relative to what they were before and relative to other regions,” Greenbaum said.

###

Rosenberg is a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. Feldman is a member of Stanford Bio-X, the Stanford Cancer Institute, the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Other Stanford co-authors on the study include Marcus Feldman, the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences, and former postdoctoral researcher Oren Kolodny, currently an assistant professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Investigators from the University of California, Berkeley, and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel also contributed to the research.

The research was funded by the Stanford Center for Computational, Evolutionary, and Human Genomics, the John Templeton Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Reference: “Disease transmission and introgression can explain the long-lasting contact zone of modern humans and Neanderthals” by Gili Greenbaum, Wayne M. Getz, Noah A. Rosenberg, Marcus W. Feldman, Erella Hovers and Oren Kolodny, 1 November 2019, Nature Communication.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-12862-7

current estimates are that adult neanderthals required 4,000 to 7,000 calories per day. modern humans, 2000 to 3,000 calories per day. seems that fact alone would eventually doom most of the neanderthal genome to oblivion.

Perhaps if anyone can prove they have Neaderthal DNA they can sue all true homosapiens for compensation for past wrongdoing. At least they have a good chance here in Canada with Trudeau at the helm.

Macbook pro socking prize ???

https://www.sarthtya.tech/2019/11/apple-laptop-macbook-pro-aplles-new.html?m=1

Neanderthals are alive and well. They’ve changed their name to “Democrat”.

The key premise of their proposition is “the unique diseases harbored by Neanderthals and modern humans could have created an invisible disease barrier that discouraged forays into enemy territory”.

This seems to be a very weak if not entirely unlikely process. 1) You do not get someone’s disease by hunting in their territory, especially when a population density is low; 2) Hunter-gatherers would not refrain from exploring new hunting areas because of a personal risk. They are quite good today and probably even better then in evaluating trade-offs between the risk and reward (think of today’s hunters stealing meat from lions); 3) Even if they perceived contacts with with the ‘others’ risky, they could exploit/move through areas the other population was periodically absent. Avoidance of direct contact does not preclude territorial penetration. That would lead to local exclusivity of habitat occupation and an overlap over a broad range at the same time.

In short, speculation on the ‘invisible’ barrier is possible but it foundation is just that – speculation, and the pattern of human behavior is inconsistent with it, especially for 20000 years.

A contemporary angle on my comment above:

One does not fail to get basic groceries because of disease – one practices social distancing while getting what is important.

No. You use grocery delivery which I use during Covid

Jurek kOlasa please run for office just a little common sense back in this world would go a long way,