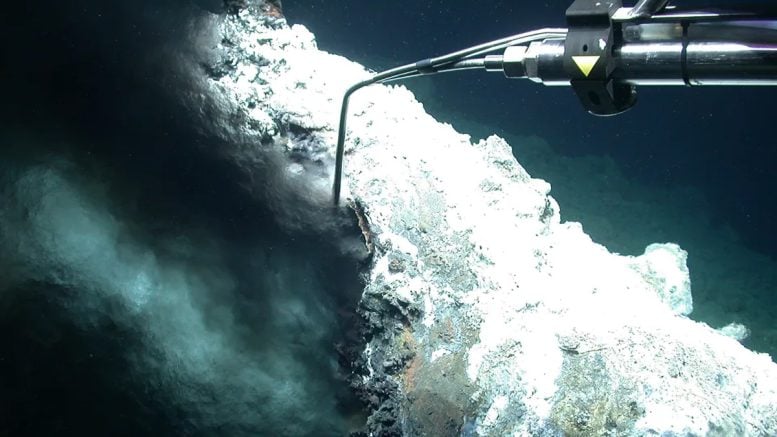

The temperature measurement at the outflow opening of the black smoker revealed fluid temperatures greater than 300°C. In addition to this active smoker, numerous different types of vent emissions were identified in the newly discovered Jøtul hydrothermal field. Credit: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen.

Hydrothermal vents are located globally at the boundaries of shifting tectonic plates, with many fields yet to be discovered. In a 2022 expedition aboard the MARIA S. MERIAN, researchers identified the first hydrothermal vent field along the 500-kilometer Knipovich Ridge near Svalbard. Led by Prof. Dr. Gerhard Bohrmann from MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and the University of Bremen’s Geosciences department, the international team, including scientists from Bremen and Norway, detailed their findings in the journal Scientific Reports.

Hydrothermal vents are seeps on the sea floor from which hot liquids escape. “Water penetrates into the ocean floor where it is heated by magma. The overheated water then rises back to the sea floor through cracks and fissures. On its way up the fluid becomes enriched in minerals and materials dissolved out of the oceanic crustal rocks. These fluids often seep out again at the sea floor through tube-like chimneys called black smokers, where metal-rich minerals are then precipitated,” explains Prof. Gerhard Bohrmann of MARUM and chief scientist of the MARIA S. MERIAN (MSM 109) expedition.

At water depths greater than 3,000 meters, the remote-controlled submersible vehicle MARUM-QUEST took samples from the newly discovered hydrothermal field. Named after Jøtul, a giant in Nordic mythology, the field is located on the 500-kilometer-long Knipovich Ridge. The ridge lies within the triangle formed by Greenland, Norway, and Svalbard on the boundary of the North American and European tectonic plates.

Among the numerous hydrothermal mounds of the Jøtul field is the Nidhogg spring, named after a serpent-like dragon in Norse mythology that lives on the world tree Yggdrasil. The fluids with temperatures of 40 to 50 degrees Celsius at Nidhogg lead to the precipitation of barite and amorphous opal, and the numerous amphipods, particularly like these temperatures. Credit: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen

This kind of plate boundary, where two plates move apart, is called a spreading ridge. The Jøtul Field is located on an extremely slow-spreading ridge with a growth rate of the plates of less than two centimeters per year. Because very little is known about hydrothermal activity on slow-spreading ridges, the expedition focused on obtaining an overview of the escaping fluids, as well as the size and composition of active and inactive smokers in the field.

Climate Impact and Methane Emissions

“The Jøtul Field is a discovery of scientific interest not only because of its location in the ocean but also due to its climate significance, which was revealed by our detection of very high concentrations of methane in the fluid samples, among other things,” reports Gerhard Bohrmann. Methane emissions from hydrothermal vents indicate a vigorous interaction of magma with sediments.

On its journey through the water column, a large proportion of the methane is converted into carbon dioxide, which increases the concentration of CO2 in the ocean and contributes to acidification, but it also has an impact on climate when it interacts with the atmosphere.

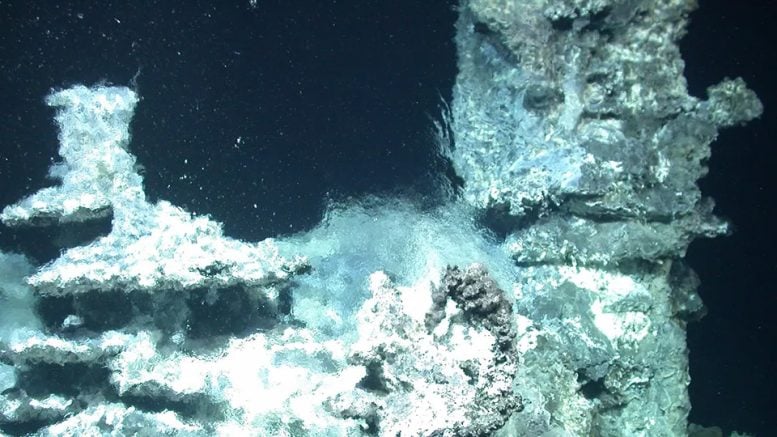

The most spectacular hydrothermal vent of the MSM109 expedition featured several chimneys and vents, and the outflowing fluid shimmered around it. This complex structure was named the Yggdrasil Hydrothermal Vent, from the name of the Tree of Life in Nordic mythology. Credit: MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen

The amount of methane from the Jøtul Field that eventually escapes directly into the atmosphere, where it then acts as a greenhouse gas, still needs to be studied in more detail. There is also little known about the organisms living chemosynthetically in the Jøtul Field. In the darkness of the deep ocean, where photosynthesis cannot occur, hydrothermal fluids form the basis for chemosynthesis, which is employed by very specific organisms in symbiosis with bacteria.

In order to significantly expand on the somewhat sparse information available on the Jøtul Field, a new expedition of the MARIA S. MERIAN will start in late summer of this year under the leadership of Gerhard Bohrmann. The focus of the expedition is the exploration and sampling of as-yet-unknown areas of the Jøtul Field. With extensive data from the Jøtul Field, it will be possible to make comparisons with the few already known hydrothermal fields in the Arctic province, such as the Aurora Field and Loki’s Castle.

Reference: “Discovery of the first hydrothermal field along the 500-km-long Knipovich Ridge offshore Svalbard (the Jøtul field)” by Gerhard Bohrmann, Katharina Streuff, Miriam Römer, Stig-Morten Knutsen, Daniel Smrzka, Jan Kleint, Aaron Röhler, Thomas Pape, Nils Rune Sandstå, Charlotte Kleint, Christian Hansen, Christian dos Santos Ferreira, Maren Walter, Gustavo Macedo de Paula Santos and Wolfgang Bach, 3 May 2024, Scientific Reports.

DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-60802-3

The published study is a part of the Bremen Cluster of Excellence “The Ocean Floor – Earth’s Uncharted Interface”, which explores complex processes on the sea floor and their impacts on global climate. The Jøtul Field will also play an important role as an object of future research in the Cluster.

“… and contributes to acidification, …”

Why not say “contributes to neutralization, …” which is at least as valid as “acidification” because an alkaline solution (sea water), whose pH is declining, has to reach a point of neutrality (pH 7) before it can become acidic.

I would suggest that the reason is that a political agenda has taken precedence over objective science. Those who piously claim that they support science, and denigrate what they insultingly call “deniers,” are demonstrating that they are rejecting the behavior of the ideal scientist, which is that of a “disinterested observer.”