University of Arizona astronomers have identified a 3-million-light-year-long galactic filament from the early universe using the James Webb Space Telescope. The study also examined eight quasars and their influence on star formation, providing insights into the assembly and growth of supermassive black holes. (Cosmic web artist’s concept.)

A string of lined-up galaxies in the early universe reveals clues – and questions – about the fundamental architecture of the universe.

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, a team of scientists led by University of Arizona astronomers has discovered a threadlike arrangement of 10 galaxies that existed just 830 million years after the Big Bang.

Lined up like pearls on an invisible string, the 3-million-light-year-long structure is anchored by a luminous quasar – a galaxy with an active, supermassive black hole at its core. The team believes the filament will eventually evolve into a massive cluster of galaxies, much like the well-known Coma Cluster in the “nearby” universe. The results are published in two papers in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“This is one of the earliest filamentary structures that people have ever found associated with a distant quasar,” said Feige Wang, an assistant research professor at the UArizona Steward Observatory and lead author of the first paper. Wang added that it is the first time a structure of this kind has been observed at such an early time in the universe and in 3D detail.

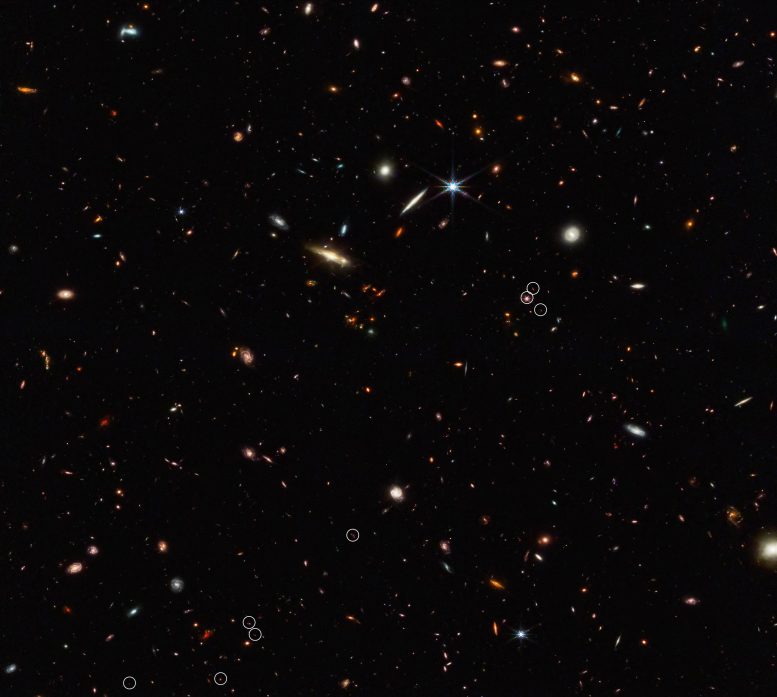

This deep galaxy field from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) shows an arrangement of 10 distant galaxies marked by eight white circles in a diagonal, thread-like line. (Two of the circles contain more than one galaxy.) This 3 million light-year-long filament is anchored by a very distant and luminous quasar – a galaxy with an active, supermassive black hole at its core. The quasar, called J0305-3150, appears in the middle of the cluster of three circles on the right side of the image. Its brightness outshines its host galaxy. The 10 marked galaxies existed just 830 million years after the big bang. The team believes the filament will eventually evolve into a massive cluster of galaxies. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Feige Wang (University of Arizona), Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

Galaxies are not scattered randomly across the universe. They gather together not only into clusters and clumps, but form vast interconnected filamentary structures, separated by gigantic barren voids in between. This “cosmic web” started out tenuous and became more distinct over time as gravity drew matter together.

Embedded in vast “oceans” of dark matter, galaxies form where dark and regular matter accumulate in localized patches that are denser than their surroundings. Similar to the crests of waves in the ocean, galaxies ride on continuous strings of dark matter known as filaments, explained Xiaohui Fan, Regents’ Professor of Astronomy at Steward and a co-author on both publications. The newly discovered filament marks the first time such a structure has been observed at a time when the cosmos was just 6% of its current age.

“I was surprised by how long and how narrow this filament is,” Fan said. “I expected to find something, but I didn’t expect such a long, distinctly thin structure.”

This discovery was made as part of the ASPIRE project, a large international collaboration led by UArizona researchers, with Wang being the principal investigator. The main goal of ASPIRE – which stands for A SPectroscopic survey of biased halos In the Reionization Era – is to study the cosmic environments of the earliest black holes. The program will observe 25 quasars that existed within the first billion years after the Big Bang, a time known as the Epoch of Reionization.

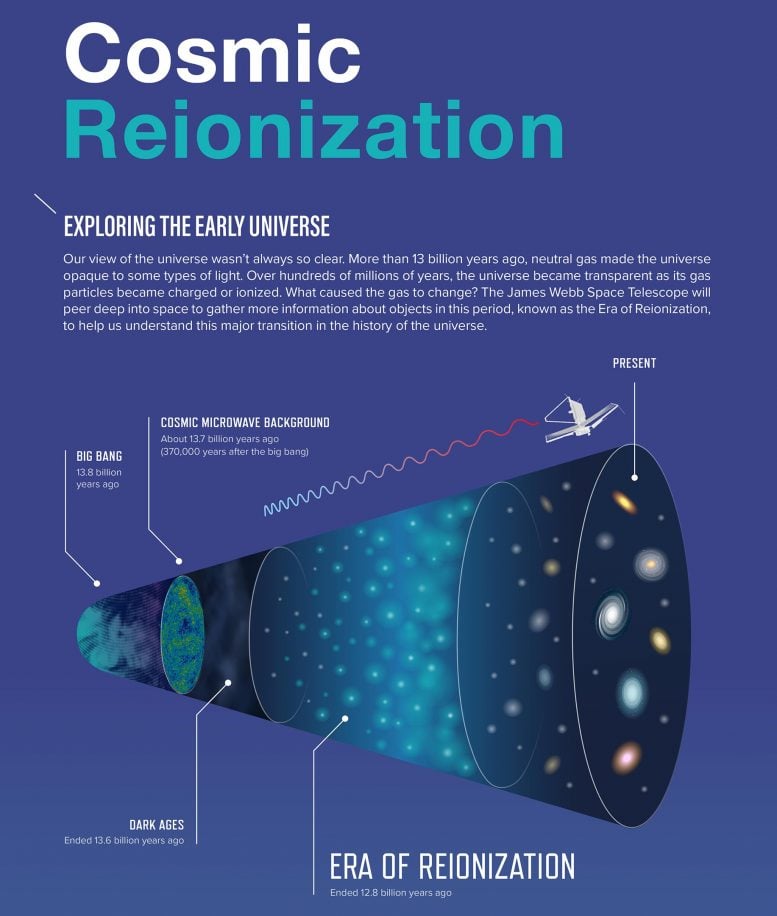

(Click image to see full infographic.) More than 13 billion years ago, during the Era of Reionization, the universe was a very different place. The gas between galaxies was largely opaque to energetic light, making it difficult to observe young galaxies. What allowed the universe to become completely ionized, or transparent, eventually leading to the “clear” conditions detected in much of the universe today? The James Webb Space Telescope will peer deep into space to gather more information about objects that existed during the Era of Reionization to help us understand this major transition in the history of the universe. Credit: NASA, ESA, and J. Kang (STScI)

“The last two decades of cosmology research have given us a robust understanding of how the cosmic web forms and evolves,” said team member Joseph Hennawi of the University of California, Santa Barbara. “ASPIRE aims to understand how to embed the emergence of the earliest massive black holes into our current story of cosmic structure formation.”

Winds of change

Another part of the study investigates the properties of eight quasars in the young universe. The team confirmed that their central black holes, which existed less than a billion years after the Big Bang, range in mass from 600 million to 2 billion times the mass of the sun. Astronomers continue seeking evidence to explain how these black holes could grow so large so fast.

To form these supermassive black holes in such a short time, two criteria must be satisfied, said Wang.

“First, you need to start growing from a massive ‘seed’ black hole,” he explained. “Two, even if this seed starts with a mass equivalent of a thousand suns, it needs to accrete a million times more matter at the maximum possible rate in a relatively short time, because our observations caught it at a time when it was still very young.”

Quasars — shown here in an artist’s illustration— are some of the brightest objects in the universe. The energy released by the quasar’s supermassive black hole as it devours mass from its surroundings is widely considered to be the main driver in limiting the growth of massive galaxies. Credit: STScI

“These unprecedented observations are providing important clues about how black holes are assembled. We have learned that these black holes are situated in massive young galaxies that provide the reservoir of fuel for their growth,” said Jinyi Yang, an assistant research professor at Steward, who is leading the study of black holes with ASPIRE and is the first author of the second publication.

The James Webb Space Telescope also provided the best evidence yet of how early supermassive black holes potentially regulate the formation of stars in their galaxies. While supermassive black holes accrete matter, they also can power tremendous outflows of material. These “winds” can extend far beyond the black hole itself, on a galactic scale, and can have a significant impact on the formation of stars. Stars form when gas and dust collapse into denser and denser clouds, and this requires the gas to be very cold. Strong winds from black holes emitting large amounts of energy can wreak havoc with that process and thereby suppress the formation of stars in the host galaxy, Yang explained.

“Such winds have been observed in the nearby universe but have never been directly observed this early in the universe, in the Epoch of Reionization,” said Yang. “The scale of the wind is related to the structure of the quasar. In the Webb observations, we are seeing that such winds extend throughout an entire galaxy, affecting its evolution.”

For more on this research, see NASA’s Webb Telescope Illuminates Earliest Strands of the Cosmic Web.

References:

“A SPectroscopic Survey of Biased Halos in the Reionization Era (ASPIRE): JWST Reveals a Filamentary Structure around a z = 6.61 Quasar” by Feige Wang, Jinyi Yang, Joseph F. Hennawi, Xiaohui Fan, Fengwu Sun, Jaclyn B. Champagne, Tiago Costa, Melanie Habouzit, Ryan Endsley, Zihao Li, Xiaojing Lin, Romain A. Meyer, Jan–Torge Schindler, Yunjing Wu, Eduardo Bañados, Aaron J. Barth, Aklant K. Bhowmick, Rebekka Bieri, Laura Blecha, Sarah Bosman, Zheng Cai, Luis Colina, Thomas Connor, Frederick B. Davies, Roberto Decarli, Gisella De Rosa, Alyssa B. Drake, Eiichi Egami, Anna-Christina Eilers, Analis E. Evans, Emanuele Paolo Farina, Zoltan Haiman, Linhua Jiang, Xiangyu Jin, Hyunsung D. Jun, Koki Kakiichi, Yana Khusanova, Girish Kulkarni, Mingyu Li, Weizhe Liu, Federica Loiacono, Alessandro Lupi, Chiara Mazzucchelli, Masafusa Onoue, Maria A. Pudoka, Sofía Rojas-Ruiz, Yue Shen, Michael A. Strauss, Wei Leong Tee, Benny Trakhtenbrot, Maxime Trebitsch, Bram Venemans, Marta Volonteri, Fabian Walter, Zhang-Liang Xie, Minghao Yue, Haowen Zhang, Huanian Zhang and Siwei Zou, 29 June 2023, The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/accd6f

“A SPectroscopic Survey of Biased Halos in the Reionization Era (ASPIRE): A First Look at the Rest-frame Optical Spectra of z > 6.5 Quasars Using JWST” by Jinyi Yang, Feige Wang, Xiaohui Fan, Joseph F. Hennawi, Aaron J. Barth, Eduardo Bañados, Fengwu Sun, Weizhe Liu, Zheng Cai, Linhua Jiang, Zihao Li, Masafusa Onoue, Jan-Torge Schindler, Yue Shen, Yunjing Wu, Aklant K. Bhowmick, Rebekka Bieri, Laura Blecha, Sarah Bosman, Jaclyn B. Champagne, Luis Colina, Thomas Connor, Tiago Costa, Frederick B. Davies, Roberto Decarli, Gisella De Rosa, Alyssa B. Drake, Eiichi Egami, Anna-Christina Eilers, Analis E. Evans, Emanuele Paolo Farina, Melanie Habouzit, Zoltan Haiman, Xiangyu Jin, Hyunsung D. Jun, Koki Kakiichi, Yana Khusanova, Girish Kulkarni, Federica Loiacono, Alessandro Lupi, Chiara Mazzucchelli, Zhiwei Pan, Sofía Rojas-Ruiz, Michael A. Strauss, Wei Leong Tee, Benny Trakhtenbrot, Maxime Trebitsch, Bram Venemans, Marianne Vestergaard, Marta Volonteri, Fabian Walter, Zhang-Liang Xie, Minghao Yue, Haowen Zhang, Huanian Zhang and Siwei Zou, 29 June 2023, The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/acc9c8

Be the first to comment on "Astronomers Use Webb Telescope To Identify the Earliest Strands of the Cosmic Web"