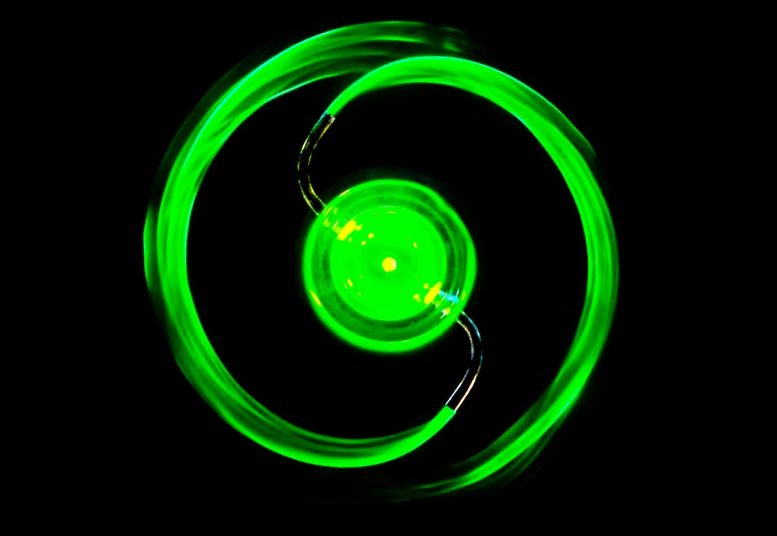

This photograph shows fluorescein dye being ejected from the sprinkler as it spins in forward mode. Credit: NYU’s Applied Mathematics Laboratory

Scientists have solved the decades-old Feynman Sprinkler Problem, showing that a sprinkler running in reverse spins oppositely to when it ejects water. This finding deepens our understanding of fluid dynamics and could inform renewable energy development.

For decades scientists have been trying to solve Feynman’s Sprinkler Problem: How does a sprinkler running in reverse—in which the water flows into the device rather than out of it—work? Through a series of experiments, a team of mathematicians has figured out how flowing fluids exert forces and move structures, thereby revealing the answer to this long-standing mystery.

“Our study solves the problem by combining precision lab experiments with mathematical modeling that explains how a reverse sprinkler operates,” explains Leif Ristroph, an associate professor at New York University’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences and the senior author of the paper, appears in the journal Physical Review Letters. “We found that the reverse sprinkler spins in the ‘reverse’ or opposite direction when taking in water as it does when ejecting it, and the cause is subtle and surprising.”

Understanding Reverse Sprinklers

“The regular or ‘forward’ sprinkler is similar to a rocket, since it propels itself by shooting out jets,” adds Ristroph. “But the reverse sprinkler is mysterious since the water being sucked in doesn’t look at all like jets. We discovered that the secret is hidden inside the sprinkler, where there are indeed jets that explain the observed motions.”

The research answers one of the oldest and most difficult problems in the physics of fluids. And while Ristroph recognizes there is modest utility in understanding the workings of a reverse sprinkler—“There is no need to ‘unwater’ lawns,” he says—the findings teach us about the underlying physics and whether we can improve the methods needed to engineer devices that use flowing fluids to control motions and forces.

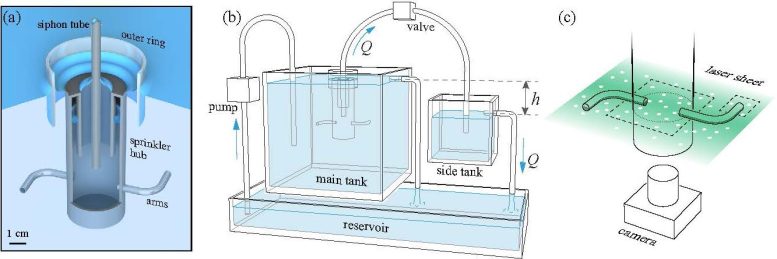

The image illustrates the experimental set-up: (a) Cut-away schematic of the floating sprinkler, (b) Flow control apparatus operating in suction mode, and (c) Flow imaging with a laser sheet illumination of particle-laden water. Credit: NYU’s Applied Mathematics Laboratory

“We now have a much better understanding about situations in which fluid flow through structures can induce motion,” notes Brennan Sprinkle, an assistant professor at Colorado School of Mines and one of the paper’s co-authors. “We think these methods we used in our experiments will be useful for many practical applications involving devices that respond to flowing air or water.”

The Feynman sprinkler problem is typically framed as a thought experiment about a type of lawn sprinkler that spins when fluid, such as water, is expelled out of its S-shaped tubes or “arms.” The question asks what happens if fluid is sucked in through the arms: Does the device rotate, in what direction, and why?

The Historical Context and Experimental Breakthrough

The problem is associated with pioneers in physics, from Ernst Mach, who posed the problem in the 1880s, to the Nobel laureate Richard Feynman, who worked on and popularized it from the 1960s through 1980s. It has since spawned numerous studies that debate the outcome and the underlying physics—and to this day it is presented as an open problem in physics and in fluid mechanics textbooks.

In setting out to solve the reverse sprinkler problem, Ristroph, Sprinkle, and their co-authors, Kaizhe Wang, an NYU doctoral student at the time of the study, and Mingxuan Zuo, an NYU graduate student, custom manufactured sprinkler devices and immersed them in water in an apparatus that pushes in or pulls out water at controllable rates. To let the device spin freely in response to the flow, the researchers built a new type of ultra-low-friction rotary bearing. They also designed the sprinkler in a way that enabled them to observe and measure how the water flows outside, inside, and through it.

“This has never been done before and was key to solving the problem,” Ristroph explains.

To better observe the reverse sprinkler process, the researchers added dyes and microparticles in the water, illuminated with lasers, and captured the flows using high-speed cameras.

The results showed that a reverse sprinkler rotates much more slowly than does a conventional one—about 50 times slower—but the mechanisms are fundamentally similar. A conventional forward sprinkler acts like a rotating version of a rocket powered by water jetting out of the arms. A reverse sprinkler acts as an “inside-out rocket,” with its jets shooting inside the chamber where the arms meet. The researchers found that the two internal jets collide but they do not meet exactly head on, and their math model showed how this subtle effect produces forces that rotate the sprinkler in reverse.

The team sees the breakthrough as potentially beneficial to harnessing climate-friendly energy sources.

“There are ample and sustainable sources of energy flowing around us—wind in our atmosphere as well as waves and currents in our oceans and rivers,” says Ristroph. “Figuring out how to harvest this energy is a major challenge and will require us to better understand the physics of fluids.”

Reference: “Centrifugal Flows Drive Reverse Rotation of Feynman’s Sprinkler” by Kaizhe Wang, Brennan Sprinkle, Mingxuan Zuo and Leif Ristroph, 26 January 2024, Physical Review Letters.

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.044003

The work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (DMS-1646339).

The Physical Review Letters (PRL) adhere to and disseminate pseudoscientific ideas. Its harm to physics has far exceeded that of general pseudoacademic publications.

The researcher’s article is published in a publication that is neither scientific nor honest. It’s really not worth showing off.

If researchers allow an untrustworthy publication to publish their research, the value and significance of the research will be greatly reduced. At the same time, the personality and qualities of the researchers are also questionable.

I hope researchers are not fooled by the pseudoscientific theories of the Physical Review Letters (PRL), and hope more people dare to stand up and fight against rampant pseudoscience.

The so-called academic journals (such as Physical Review Letters, Nature, Science, etc.) firmly believe that two objects (such as two sets of cobalt-60) of high-dimensional spacetime rotating in opposite directions can be transformed into two objects that mirror each other, is a typical case of pseudoscience rampant.

If researchers are really interested in Science and Physics, you can browse https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/643404671 and https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/595280873.

The interaction of topological vortices gives humanity infinite possibilities. If you are interested, you can browse https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/390071860 and https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/463666584.

Standing on the outside looking in. Psuedo grasping what the heck issue is. ????? . Shalom.

Interesting project. I have a fan that blows air from its front, the “front” as frame of reference perceive by me by me when looking at it front the front.To blow air from the the front the fan spins in a clockwise direction. To do so it sucks in air from the back of the fan as the back is perceived me when looking at the fan from its front. Clearly, to suck in air the fan has to spin an anticlockwise direction whilst spinning in a clockwise direction……………..

It would seem that lawn sprinklers are different…………….?

Questions about galaxies likely had a role in generating Feynman’s sprinkler puzzle. Some people look at other hydrodynamics-based gravity models. The most interesting points of focus to me here are the arm bend flow-deflection reactions and the reversed outlet flows. Not all of the inflow begins as if aimed at the reversed sprinkler heads, as some inflow can climb along the arms as it moves toward the inlets. Immersion diminishes the arm-bend flow-deflection reactions.

The most curious aspect of this story is the name of one author: Brennan Sprinkle.