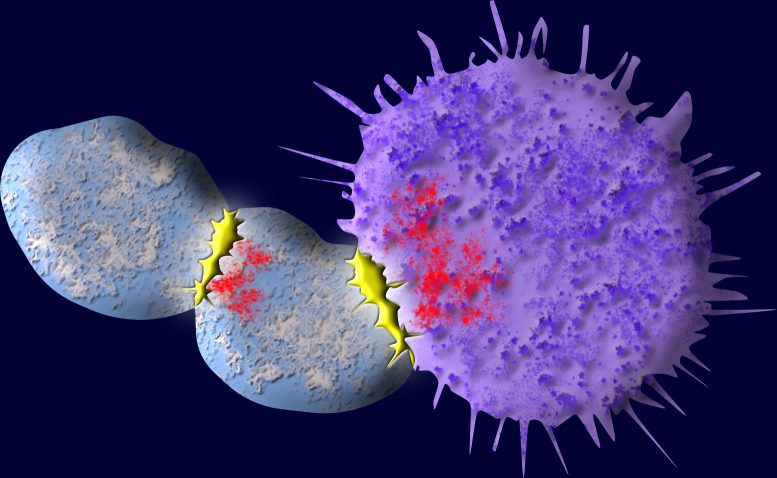

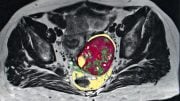

In CAR-T therapy, T cells in blue find antigens (red) and kill cancer cells (purple). But often, antigens attach to other T cells leading other T cells to attack their brothers and sisters. Credit: Xiaoyu (Ariel) Zhou

New recent research from Yale has discovered a method to control the self-destructive tendencies of certain killer T cells utilized in cancer therapy.

CAR T-cell (chimeric antigen receptor) therapy, a promising form of immunotherapy, involves reprogramming the patient’s T cells to enhance their ability to identify and combat antigens on the surface of cancer cells.

However, this therapy, which is currently approved for the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma, has a significant downside. During the process of destroying cancer cells, many of the engineered T cells get contaminated with residual cancer antigens, leading them to attack fellow T cells. This eventually results in a decrease in the body’s population of cancer-fighting cells, opening the door for a recurrence of cancer.

A new Yale study, however, has identified a way to tame the self-destructive tendencies of these killer T cells. Simply fusing a molecular tail onto the engineered T cells used in therapy, researchers say, can inhibit their proclivity to attack each other. The study was published July 27 in the journal Nature Immunology.

“It’s like putting a sword back in the sheath after it has done its work,’’ said Sidi Chen, associate professor of genetics at Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study.

For the study, the Yale team — which was led by co-first authors Xiaoyu Zhou and Hanbing Cao — fused CTLA-4 cytoplasmic tails (CCTs) to engineered CAR T cells. CCTs are a portion of a naturally occurring human protein, known as CTLA-4, which is known to keep the immune system in check by regulating T cells. Researchers observed that the cells fused with these tails were less exhausted and survived longer than CAR T cells without the tails.

“The CAR T cells with the engineered tails were less reactive but more persistent” in killing cancer cells, said Zhou, a postdoctoral associate in Chen’s lab.

Chen says it would be relatively easy for existing companies to fuse CCTs to CAR T cells, and that improvements in therapy might help expand treatments to solid tumors as well.

Reference: “CTLA-4 tail fusion enhances CAR-T antitumor immunity” by Xiaoyu Zhou, Hanbing Cao, Shao-Yu Fang, Ryan D. Chow, Kaiyuan Tang, Medha Majety, Meizhu Bai, Matthew B. Dong, Paul A. Renauer, Xingbo Shang, Kazushi Suzuki, Andre Levchenko and Sidi Chen, 27 July 2023, Nature Immunology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41590-023-01571-5

Chen is affiliated with the Yale Cancer Center, the Yale Stem Cell Center, the Yale Center for Biomedical Data Science, and the Systems Biology Institute and Center for Cancer Systems Biology at Yale’s West Campus. The work is supported by National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Defense, and several foundations.

Be the first to comment on "Cancer Breakthrough: Yale Scientists Discover New Way To Reduce Friendly Fire in Cell Therapy"