Scientists have developed a method to rapidly obtain valuable information about the risk of a volcano erupting by analyzing three key parameters: the height of the volcano, the thickness of the rock layer separating the volcano’s reservoir from the surface, and the average chemical composition of the magma. This method opens new prospects for identifying and monitoring active volcanoes that present the greatest risk, without the need for major technical and financial resources.

A team from UNIGE has identified three easily measurable parameters that offer insights into the structural characteristics of volcanoes, marking progress in the area of risk evaluation and preventive measures.

What is the risk of a volcano erupting? To assess the likelihood of a volcanic eruption, researchers require insights into the volcano’s internal architecture. However, acquiring this essential data can be a long-term undertaking, involving years of field studies, analyses, and continuous monitoring. This is why only a fraction—approximately 30%—of active volcanoes are currently well documented.

A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has developed a method for rapidly obtaining valuable information. Their approach focuses on three key variables: the volcano’s elevation, the depth of the rock layer that separates the magma chamber from the surface, and the magma’s average chemical makeup. Published in the journal Geology, these findings offer new avenues for identifying volcanoes that pose the most significant risks.

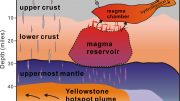

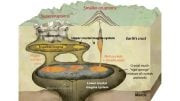

The Earth is home to some 1,500 active volcanoes, yet we only have accurate data for 30% of them. This is due to the difficulty of observing their “fuel”, the famous magma, which is rich in information. This molten rock is first generated at a depth of between 60 km and 150 km in the Earth’s mantle, whereas the deepest human boreholes generally only reach a depth of around ten kilometers (6.2 miles), preventing direct observation. The production rate of magma in the Earth’s deep crust beneath a volcano determines the size and frequency of future eruptions.

Mt Liamuiga on the Island state of St Kitts and Nevis. It is one of the main volcanoes studied by Luca Caricchi and his team. Credit: Oliver Higgins

This lack of data is a danger as more than 800 million people live close to active volcanoes. Therefore, in many regions, there is no basis on which to assess the risk a given volcano poses and the extent of the protective measures to be taken – the evacuation perimeter, for example – in the event of a suspected eruption.

Three key parameters

Geochemical and geophysical analysis methods are regularly used by scientists to monitor volcanoes, but it can take decades to gain an in-depth understanding of how a specific volcano works. Thanks to recent work by the team of Luca Caricchi, full professor at the Department of Earth Sciences of the UNIGE Faculty of Science, it is now possible to obtain valuable information more rapidly.

This method uses three easy-to-measure parameters: the height of the volcano, the thickness of the rocks separating the volcano’s “reservoir” from the surface, and the chemical composition of the magma released over its eruptive history. The first can be determined by satellite, the second by geophysics and/or chemical analysis of minerals (crystals) in the volcanic rocks, and the third by direct sampling in the field.

A “snapshot”

By analyzing existing data on the volcanic arc of the Lesser Antilles, a well-studied archipelago of volcanic islands, the UNIGE team has highlighted a correlation between the height of volcanoes and the rate at which magma is produced. “The highest volcanoes produce the biggest eruptions on average during their life. In other words, they can erupt a greater quantity of magma in a single event”, explains Oliver Higgins, a former doctoral student in Luca Caricchi’s group and first author of the study.

Scientists have also found that the thinner the Earth’s crust beneath the volcano, the closer its magma reservoir is to the surface, and the more thermally mature the volcano is. “When the magma rises from depth, it tends to cool and solidify, which halts its ascent. But when the supply of magma is large, magma retains its temperature, accumulates in the reservoir that will fuel a future eruption, and ‘eats away’ at the Earth’s crust”, explains Luca Caricchi, the second and last author of the study.

Identifying the volcanoes most at risk

Finally, the researchers observed that the average chemical composition of magma that has already erupted is an indicator of its explosiveness. “High levels of silica, for example, indicate that the volcano is fed by large quantities of magma. In this case, there is a greater risk of a large, explosive eruption from that volcano”, explains the researcher.

Together, the three parameters identified by the UNIGE team produce a “snapshot” of a volcano’s internal structure. They enable an initial assessment of the hazard associated with poorly studied volcanoes, without the need for major technical and financial resources. This method can be used to identify the active volcanoes that are most likely to produce a large-scale eruption, and that require increased surveillance.

Reference: “Eruptive dynamics reflect crustal structure and mantle productivity beneath volcanoes” by Oliver Higgins and Luca Caricchi, 11 August 2023, Geology.

DOI: 10.1130/G51355.1

Be the first to comment on "Deciphering Volcanic Secrets: A Groundbreaking New Method To Predict Eruptions"