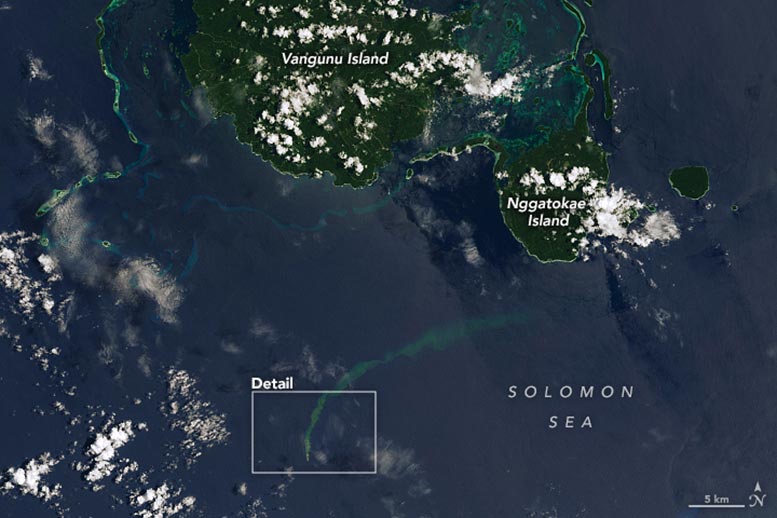

Satellite image of a plume of discolored water near the Kavachi undersea volcano captured on March 8, 2024, by the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8.

A Landsat satellite acquired this image of discolored water drifting from the active underwater volcano.

Kavachi is one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the Pacific. This conical seamount, located in the Solomon Islands and named after a sea god of the Gatokae and Vangunu people, rises some 1,200 meters (3,900 feet) from the seafloor. But its summit remains just 20 meters (65 feet) below sea level, which makes it easier for satellites to detect discolorations of the water due to volcanic activity than at deeper undersea volcanoes.

Volcanic Activity and Observations

Kavachi has erupted at least 39 times since 1939, with the latest eruptive period beginning in 2021, according to the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program. In 2024, the volcano continued to stir—and satellites continued to capture images of discolored plumes of water.

The image above, acquired on March 8 by the OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8, shows a plume of discolored water near the undersea volcano. The plume drifted north-northeast toward Nggatokae Island. Vangunu Island, also pictured, lies about 24 kilometers (15 miles) north of Kavachi, and Papua New Guinea is about 800 kilometers (500 miles) to the west.

The MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) on NASA’s Terra and Aqua captured images of similar underwater plumes near Kavachi on several other occasions in recent weeks, including February 3, 15, and 23.

Scientific Research and Findings

Previous research has shown such plumes of superheated, acidic water can contain particulate matter, volcanic rock fragments, and sulfur, as well as precipitates of silicon, iron, and aluminum oxides. The color of plumes can offer clues about the composition of the particles within them. Yellow and brown plumes tend to have a higher proportion of iron, while white plumes tend to have a higher proportion of silicon or aluminum.

Though Kavachi is challenging for scientists to access, a lull in activity allowed a team to explore it in 2015. The researchers observed marine life within the crater, including orange and white bacterial mats, silky and hammerhead sharks, bluefin trevally, and snapper.

The authors of a report about the expedition noted that other active submarine volcanos—Vailulu’u Seamount in American Samoa and Kolumbo in Greece—are known to have highly acidic water and “kill zones” that contain carcasses of larger animals. “It is likely that the high crater walls at these sites cause physical entrainment and concentration of vent fluids, while Kavachi’s crater is relatively shallow and subjected to high surface currents that allow rapid mixing to occur,” they wrote in the report.

Geological Context and Characteristics

Kavachi formed in a tectonically active area just 30 kilometers (18 miles) northeast of a subduction zone. The volcano produces lavas that range from basaltic, which is rich in magnesium and iron, to andesitic, which contains more silica. It is known for having phreatomagmatic eruptions in which the interaction of magma and water eject steam, ash, volcanic rock fragments, and incandescent bombs out of the water and into the air.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Be the first to comment on "Diving Into Kavachi’s Fury: Unraveling the Mysteries of an Undersea Volcano"