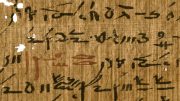

The front of the artifact. The front side depicts the head of a figure whose face is, unfortunately, missing, with the remains of a fan directly behind. Traces of hieroglyphs are also present above the head.

Swansea University Egyptology lecturer Dr. Ken Griffin has found a depiction of one of the most famous pharaohs in history Hatshepsut (one of only a handful of female pharaohs) on an object in the Egypt Center stores, which had been chosen for an object handling session.

The opportunity to handle genuine Egyptian artifacts is provided by the Egypt Center to students studying Egyptology at Swansea University. During a recent handling session for an Egyptian Art and Architecture module Dr. Kenneth Griffin, from the University’s Department of Classics, Ancient History and Egyptology, noticed that one of the objects chosen was much more interesting than initially thought.

Consisting of two irregularly shaped limestone fragments that have been glued together, the object had been kept in storage for over twenty years and was requested for the handling session based only on an old black and white photograph.

The front side depicts the head of a figure whose face is, unfortunately, missing, with the remains of a fan directly behind. Traces of hieroglyphs are also present above the head. The iconography of the piece indicates that it represents a ruler of Egypt, particularly with the presence of the uraeus (cobra) on the forehead of the figure. Who is this mysterious pharaoh and where did the fragment originate from?

A search of the Egypt Center records provides no information on the original provenance or find spot of the object. What is known is that it came to Swansea in 1971 as part of the distribution of objects belonging to Sir Henry Wellcome (1853–1936), the pharmaceutical entrepreneur based in London. The fragments are less than 5cm thick and had clearly been removed from the wall of a temple or tomb, as can be seen from the cut marks on the back.

Having visited Egypt on over fifty occasions, Dr. Griffin quickly recognized the iconography as being similar to reliefs within the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri (Luxor), which was constructed during the height of the New Kingdom. In particular, the treatment of the hair, the fillet headband with twisted uraeus, and the decoration of the fan are all well-known at Deir el-Bahri. Most importantly, the hieroglyphs above the head—part of a formulaic text attested elsewhere at the temple—use a feminine pronoun, a clear indication that the figure is female.

Hatshepsut was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty (c.1478–1458 BC) and one of only a handful of women to have held this position. Early in her reign she was represented as a female wearing a long dress, but she gradually took on more masculine traits, including being depicted with a beard. The reign of Hatshepsut was one of peace and prosperity, which allowed her to construct monuments throughout Egypt. Her memorial temple at Deir el-Bahri, built to celebrate and maintain her cult, is a masterpiece of Egyptian architecture.

Many fragments were taken from this site during the late nineteenth century, before the temple was excavated by the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Egypt Exploration Society) between 1902–1909. Since 1961 the Polish Archaeological Mission to Egypt has been excavating, restoring, and recording the temple.

Yet the mystery of the precious find doesn’t end there. On the rear of the upper fragment, the head of a man with a short beard is depicted. Initially, there was no explanation for this, but it is now clear that the upper fragment had been removed and recarved in more recent times in order to complete the face of the lower fragment. The replacement of the fragment below the figure would also explain the unusual cut of the upper fragment. This was probably done by an antique dealer, auctioneer, or even the previous owner of the piece in order to increase its value and attractiveness. It was eventually decided at an unknown date to glue the fragments together in the original layout, which is how they now appear.

While Deir el-Bahri seems the most likely provenance for this artifact, further research is needed in order to confirm this and it may even be possible to one day determine the exact spot the fragments originated from.

Given the importance of the object, the head of Hatshepsut has now been placed on display in a prominent position within the House of Life at the Egypt Center so that the relief can be appreciated by visitors to the Center.

Dr. Griffin said:

“The Egypt Center is a wonderful resource and is certainly one of the major factors in attracting students to study Egyptology at Swansea University.”

“The identification of the object as depicting Hatshepsut caused great excitement amongst the students. After all, it was only through conducting handling sessions for them that this discovery came to light.”

“While most of the students have never visited Egypt before, the handling sessions help to bring Egypt to them.”

Quotes from 2nd year Egyptology undergraduate students:

Aimee Vickery said: “I have lived in Swansea all of my life and have visited (and continue to visit) the Egypt Center on a regular basis. It is this interaction with ancient Egyptian objects that led to my passion to study Egyptology at Swansea University. As part of my course, I participate in handling sessions with other classmates. These sessions provide in-depth detail about the objects at the Egypt Center, and a chance to hold and observe the objects in a new light. I was a part of the handling session that took place when the discovery was made about the Hatshepsut fragment, and I am so pleased about the development! I am so lucky to have been a part of this wonderful discovery, and without the opportunity to handle the objects at the Egypt Center, is it unlikely that the discovery would have been made.”

Jamie Burns said: “As an Egyptology student, this discovery is of remarkable significance to me. I have been enamored with Egypt since I was extremely young and to be involved with identifying this fragment as Hatshepsut is extremely exciting. It truly feels like I am part of writing history. The Egypt Center, where this artifact resides, is a great boon to prospect Egyptologists such as myself. This in particular is why I chose to study at Swansea, as having a location with an array of artifacts on display is a unique opportunity. In addition, it is thanks to the handling sessions ran by Dr. Griffin that we are able to touch and feel the history as opposed to simply studying it, this adds an unparalleled amount of depth to my studies. This discovery is something I will look back on when I am older and consider it as one of the most important moments in my study.”

Catherine Bishop said: “Being from Swansea, I have always been able to visit the Egypt Center, giving extra opportunities throughout my childhood. I was able to study there during my A-Levels, analyzing some of the objects, which sparked my interest in Egyptology, which I am currently studying. The handling sessions held by the department have been very insightful and it’s an opportunity for hands-on contact which very few universities offer, especially to the extent to which the Egypt Center provides. The discovery of the Hatshepsut fragment has been a highlight of the course, in particular, being able to see how research develops from an original theory, all the way through to an insightful discovery!”

Unglue them, flip the top piece and fit the pieces back together. The short beard is because it IS a woman depicted. The curve of the piece fits exactly, especially at the nose. Well done, you found her!