Bio-computing is now a reality, prompting experts to call for its responsible application. The creators of DishBrain, in collaboration with bioethicists, address its ethical implications, potential medical benefits, and environmental advantages in a recent paper.

Inventors of brain-cell-based computers collaborate with a global team of ethicists to examine the ethical applications of bio-computing.

Bio-computing, once a concept confined to science fiction, is now a reality. As such, it’s crucial to begin contemplating its ethical research and application, according to a global assembly of specialists.

The creators of DishBrain have collaborated with bioethicists and medical scientists to outline a comprehensive framework. Their insights and recommendations on addressing this emerging field can be found in a recently published article in Biotechnology Advances.

“Combining biological neural systems with silicon substrates to produce intelligence-like behavior has significant promise, but we need to proceed with the bigger picture in mind to ensure sustainable progress,” says lead author Dr. Brett Kagan, Chief Scientific Officer of biotech start-up Cortical Lab. The group was made famous by their development of DishBrain – a collection of 800,000 living brain cells in a dish that learned to play Pong.

Philosophical and Ethical Questions

While philosophers have for centuries pondered concepts of what makes us human or conscious, co-author and Uehiro Chair in Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford, Professor Julian Savulescu, warns of the urgency to determine practical answers to these questions.

“We haven’t adequately addressed the moral issues of what is even considered ‘conscious’ in the context of today’s technology,” he says.

“As it stands, there are still many ways of describing consciousness or intelligence, each raising different implications for how we think about biologically based intelligent systems.”

The paper cites early English philosopher Jeremy Bentham who argued that, with respect to the moral status of animals, “the question is not, ‘can they reason?’ nor, ‘can they talk?’ but, ‘can they suffer?’”

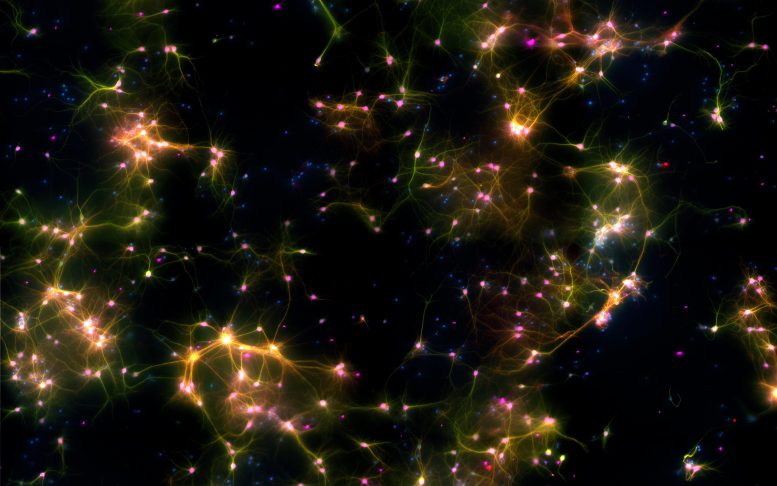

A microscopy image of neural cells where fluorescent markers show different types of cells. Green marks neurons and axons, purple marks neurons, red marks dendrites, and blue marks all cells. Where multiple markers are present, colours are merged and typically appear as yellow or pink depending on the proportion of markers. Credit:

Cortical Labs

“From that perspective, even if new biologically based computers show human-like intelligence, it does not necessarily follow that they have moral status,” says co-author Dr Tamra Lysaght, Director of Research at the Centre for Biomedical Ethics, National University of Singapore.

“Our paper doesn’t attempt to definitively answer the full suite of moral questions posed by bio-computers, but it provides a starting framework to ensure that the technology can continue to be researched and applied responsibly,” says Dr Lysaght.

Potential Medical Benefits and Challenges

The paper further highlights the ethical challenges and opportunities offered by DishBrain’s potential to greatly accelerate our understanding of diseases such as epilepsy and dementia.

“Current cell lines used in medical research predominately have European-type genetic ancestry, potentially making it harder to identify genetic-linked side effects,” says co-author Dr Christopher Gyngell, Research Fellow in biomedical ethics from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and The University of Melbourne.

Dr. Bret Kagan, Cortical Labs. Credit: Cortical Labs

“In future models of drug screening, we have the chance to make them more sufficiently representative of the real-world patients by using more diverse cell lines, and that means potentially faster and better drug development.”

Environmental Considerations

The researchers point out that it is worth working through these moral issues, as the potential impact of bio-computing is significant.

“Silicon-based computing is massively energy-hungry with a supercomputer consuming millions of watts of energy. By contrast, the human brain uses as little as 20 watts of energy – biological intelligences will show similar energy efficiency,” says Dr Kagan.

“As it stands, the IT industry is a massive contributor to carbon emissions. If even a relatively small number of processing tasks could be done with bio-computers, there is a compelling environmental reason to explore these alternatives.”

Reference: “The technology, opportunities, and challenges of Synthetic Biological Intelligence” by Brett J. Kagan, Christopher Gyngell, Tamra Lysaght, Victor M. Cole, Tsutomu Sawai and Julian Savulescu, 7 August 2023, Biotechnology Advances.

DOI: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2023.108233

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust, the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council, and the Victorian State Government.

I didn’t expect such a philosophical article. Bentham would have concerns about the brain suffering, but probably would have the most charitable system of ethics for this usage; his hedonic calculus makes the calculation simple by making everyone else happy. That’s probably why the article picked him, as few people go to Bentham first for moral judgments. I think utilitarianism would be satisfied by the utility, though rule-utilitarians might say it shouldn’t be done in general when there’s uncertainty about exactly what or whom is being manipulated. This gets in deep trouble with other ethical systems, with Kant probably considering this slavery using a constructed being as a means to an end (instead of an end in itself). I think Hume would consider this ghastly, with our obvious unease with the topic, like with Frankenstein (the monster’s name, XKCD). Descartes would consider these scientists to be evil demons, deus deceptor evil geniuses just for controlling a thinking being’s awareness, let alone forcing it to perform tasks. If anyone cares to criticize these ideas, remember I’m writing a dozen words per ethical system, instead of a dozen 5000-word comments, so there may be gaps in each argument.

Using climate change at the end as the lens to see this story through was absurd.

There seems to be no end to what environmental zealots will claim to justify the imposition of their ‘morality’ on others.

That’s a good point. The choice of Bentham’s Hedonism was striking, since it lets you to do whatever you want, as long as you want it enough. If the happiness created outweighs the suffering, it justifies anything. If they really really want this to fight climate change no matter what, Bentham’s is the ethical system to choose as justification.

I can’t think of another ethical system that would justify it, even goofy ones. It wouldn’t work in solipsism because of the uncertainty of it. LaVey would worry about the lack of love it shows and the theft, though in his Pentagonal Revisionism it could be a wonderful “artificial human companions” of “slaves”, yet any philosopher going to the Church of Satan for justification would get giggles.

I thought it was just a current-news-thing coda, and was glad they didn’t choose assault weapons or Ukraine or transgenderism. But then, the obvious link-up would be anti-racism, since they would be literally creating a race of enslaved beings disproportionately forced to play Pong.

While I don’t know of any instances where it has been used, I have long believed that “The greatest good for the greatest number of people,” could be used to justify slavery. Therefore, I have concluded that it is not a maxim to be followed.

The greatest good is pure Utilitarianism, John Stewart Mill. If killing a million people saves a billion lives, then killing has the most utility and must be done. Rule-utilitarianism recognized that problem, where not murdering is a good rule-of-thumb, best to avoid. I thought Neo-environmentalism and modern governments were utilitarian, willing to sacrifice this “Brain in a dish” and anyone else to serve everyone else. But Mill considered the valuable utility of justice and human rights too, and was vehemently anti-slavery. It makes sense that they are actually Benthamites, concerned with creating the most happiness, by doing what makes them feel best, with the ethics of hedonism.

You sound like a Kantian. Kant’s ideas aren’t fashionable anymore, but his is my favourite ethical system. In a nutshell, he had two basic maxims or rules. People should treat each-other as ends in themselves, instead of just as a means to an end. Also, an action is moral only if it could be made into a rule everyone had to follow. His system struggles when an action it considers moral has predictably bad results, but it’s a system of ethics and not results. I like the simplicity and universalizability. “Human brains should be made to perform tasks for us more efficiently” would violate both maxims, making it unethical.

There’s actually a branch of philosophy that considers this exact problem. Descartes’ ideas were adapted into “Brain in a Vat” problems in the 20th century. Usually it’s still in his terms, thought experiments considering how our reality could just be a simulation. I don’t think it was ever considered deeply in ethical terms, as it’s always a hypothetical mad scientist or demonic evil god doing it, so the fact that we are is surreal, an evil by almost any standard. Even Aristotle would say a virtuous man would not do this. It’s so absurd that I think only science-fiction has considered it deeply, particularly cyberpunk, like The Matrix, and they’re virtually all dystopian, apart from Star Trek “The Measure of a Man”.

Not being a philosopher, nor really even a student of philosophy, just a cast off from the Humanities Honors Program, I’m not intimately familiar with all the various philosophies. I’m impressed with how well the Ancient Greeks understood human psychology and integrated it into their philosophies, such as Aristotle’s definition of ‘virtue.’

For decades, I have tried to live my life by a variant of the Golden Rule: “Consider what the world would be like if everyone were to act as I’m about to. Would that be a world I would want to live in?”

Speaking practically, any rights claimed by an entity only exist if the claimant can enforce the exercise of the rights. Otherwise, the best they can hope for is protections afforded by those who have the power and means to enforce the protections. Obviously, if an entity cannot conceive of the abstraction of a right, they cannot claim to have it. However, an animal may instinctively try to exercise the rights of “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness.” However, struggling against humans, they usually lose unless the human acknowledges the right and ceases to try to impose their will.