Reforestation in the eastern U.S. has been shown to mitigate regional warming trends, with research highlighting forests’ significant cooling effects on both land and air temperatures. This underscores the potential of reforestation as a tool for climate adaptation and mitigation.

Much of the U.S. warmed during the 20th century, but the eastern part of the country remained mysteriously cool. The recovery of forests could explain why.

Widespread 20th-century reforestation in the eastern United States helped counter rising temperatures due to climate change, according to new research. The authors highlight the potential of forests as regional climate adaptation tools, which are needed along with a decrease in carbon emissions.

“It’s all about figuring out how much forests can cool down our environment and the extent of the effect,” said Mallory Barnes, lead author of the study and an environmental scientist at Indiana University. “This knowledge is key not only for large-scale reforestation projections aimed at climate mitigation, but also for initiatives like urban tree planting.”

The study was published in the AGU journal Earth’s Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present, and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

Historical Context of Eastern U.S. Reforestation

Before European colonization, the eastern United States was almost entirely covered in temperate forests. From the late 18th to early 20th centuries, timber harvests and clearing for agriculture led to forest losses exceeding 90% in some areas. In the 1930s, efforts to revive the forests, coupled with the abandonment and subsequent reforestation of subpar agricultural fields, kicked off an almost century-long comeback for eastern forests. About 15 million hectares of forest have since grown in these areas.

“The extent of the deforestation that happened in the eastern United States is remarkable, and the consequences were grave,” said Kim Novick, an environmental scientist at Indiana University and co-author of the new study. “It was a dramatic land cover change, and not that long ago.”

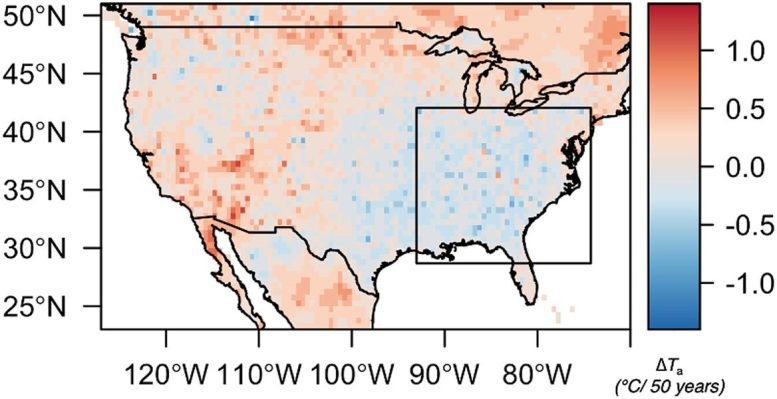

During the period of regrowth, global warming was well underway, with temperatures across North America rising 0.7 degrees Celsius (1.23 degrees Fahrenheit) on average. In contrast, from 1900 to 2000, the East Coast and Southeast cooled by about 0.3 degrees Celsius (0.5 degrees Fahrenheit), with the strongest cooling in the southeast.

Previous studies suggested the cooling could be caused by aerosols, agricultural activity or increased precipitation, but many of these factors would only explain highly localized cooling. Despite known relationships between forests and cooling, studies had not considered forests as a possible explanation for the anomalous, widespread cooling.

“This widespread history of reforestation, a huge shift in land cover, hasn’t been widely studied for how it could’ve contributed to the anomalous lack of warming in the eastern U.S., which climate scientists call a ‘warming hole,’” Barnes said. “That’s why we initially set out to do this work.”

Analyzing the Cooling Effect of Forests

Barnes, Novick, and their team used a combination of data from satellites and 58 meteorological towers to compare forests to nearby grasslands and croplands, allowing an examination of how changes in forest cover can influence ground surface temperatures and in the few meters of air right above the surface.

The researchers found that forests in the eastern U.S. today cool the land’s surface by 1 to 2 degrees Celsius (1.8 to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) annually. The strongest cooling effect occurs at midday in the summer, when trees lower temperatures by 2 to 5 degrees Celsius (3.6 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit) — providing relief when it’s needed most.

Using data from a network of gas-measuring towers, the team showed that this cooling effect also extends to the air, with forests lowering the near-surface air temperature by up to 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) during midday. (Previous work on trees’ cooling effect has focused on land, not air, temperatures.)

The team then used historic land cover and daily weather data from 398 weather stations to track the relationship between forest cover and land and near-surface air temperatures from 1900 to 2010. They found that by the end of the 20th century, weather stations surrounded by forests were up to 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than locations that did not undergo reforestation. Spots up to 300 meters (984 feet) away were also cooled, suggesting the cooling effect of reforestation could have extended even to unforested parts of the landscape.

Other factors, such as changes in agricultural irrigation, may have also had a cooling effect on the study region. The reforestation of the eastern United States in the 20th century likely contributed to, but cannot fully explain, the cooling anomaly, the authors said.

“It’s exciting to be able to contribute additional information to the long-standing and perplexing question of, ‘Why hasn’t the eastern United States warmed at a rate commensurate with the rest of the world?’” Barnes said. “We can’t explain all of the cooling, but we propose that reforestation is an important part of the story.”

Implications for Climate Adaptation Strategies

Reforestation in the eastern United States is generally regarded as a viable strategy for climate mitigation due to the capacity of these forests to sequester and store carbon. The authors note that their work suggests that eastern United States reforestation also represents an important tool for climate adaptation.

However, in different environments, such as snow-covered boreal regions, adding trees could have a warming effect. In some locations, reforestation can also affect precipitation, cloud cover, and other regional scale processes in ways that may or may not be beneficial. Land managers must therefore consider other environmental factors when evaluating the utility of forests as a climate adaptation tool.

Reference: “A Century of Reforestation Reduced Anthropogenic Warming in the Eastern United States” by Mallory L. Barnes, Quan Zhang, Scott M. Robeson, Lily Young, Elizabeth A. Burakowski, A. Christopher. Oishi, Paul C. Stoy, Gaby Katul and Kimberly A. Novick, 13 February 2024, Earth’s Future.

DOI: 10.1029/2023EF003663

It looks to me like a case is being made that land-use changes are more important than anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Basically, the claim seems to be that where trees have come back, there has been little to no change in temperatures, despite a significant increase in global CO2. I think that Lucy has got some ‘splainin’ to do.

Forests keep the amount of sunlight hitting the ground reduced, and the trees keep the snow from melting until later in the spring. CO2 is now being added back to concrete in the mixer trucks, but only in the US perimeter states along the East, South, and West coastal areas. Why Not in every state ? Reducing Portland cement and adding crushed limestone reduces our CO2 Footprint. The world eventually does what the US does so let’s do it right.

It seems that you accept that CO2 is totally responsible and are focusing on that. The point I was making was that once the forests were back to about their original level, the regional temperatures were essentially the same as before deforestation. That is in spite of a large increase in CO2! How is it that CO2 is responsible for warming if there is no net increase in temperatures where the forests have regenerated?

The cooling off was similar when the black death killed off about 2/3 rds of the Humans in Europe. Trees grew where they had been cut down for agriculture. A couple of hundred years later when Humans recovered, and cut down the trees again, it got warmer again. If we restrict the total area that can be deforested, then it will stay a little wetter, and a little cooler. Also we need to pump the sea water to the basins in the basin and range so it will increase the evaporation, add rainfall, add snowfall, and also make it a little cooler. We need between 4,000 and 5,000 square miles of lakes East of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

You are OK with sterilizing the soil in the Basin and Range province and killing all the vegetation that will be submerged, and, at best, displacing the animals and insects that currently live where you want to place lakes? Incidentally, the submerged vegetation will contribute increased carbon dioxide and methane for several decades as it decomposes. I thought that you believed CO2 is responsible for warming? Why would you want to increase it?