A study revealed that mutations in the TTN gene contribute to 18% of sporadic and 25% of familial cases of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).

The use of modern DNA sequencing platforms has helped researchers find a genetic explanation for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). Researchers at Harvard Medical School found that mutations in the gene TTN account for 18 percent of sporadic and 25 percent of familial DCM.

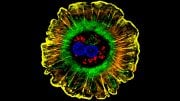

For decades, researchers have sought a genetic explanation for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), a weakening and enlargement of the heart that puts an estimated 1.6 million Americans at risk of heart failure each year. Because idiopathic DCM occurs as a familial disorder, researchers have long searched for genetic causes, but for most patients the etiology for their heart disease remained unknown.

Now, new work from the lab of Christine Seidman, a Howard Hughes Investigator and the Thomas W. Smith Professor of Medicine and Genetics at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Jonathan Seidman, the Henrietta B. and Frederick H. Bugher Foundation Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, has found that mutations in the gene TTN account for 18 percent of sporadic and 25 percent of familial DCM.

“Until the development of modern DNA sequencing platforms, the enourmous size of the TTN gene prevented a comprehensive analyses – but now we know TTN is a major cause of DCM,” said Christine Seidman, who reported the findings February 16 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Idiopathic DCM is one of three different types of cardiomyopathy (the term “idiopathic” indicates that acquired causes for DCM such as atherosclerosis, excess drinking or viral infections have been excluded). It affects only about 4 in 10,000 Americans, but may be under-diagnosed because symptoms often appear late in the course of disease. DCM may cause shortness of breath, chest pain, and limited exercise capacity. DCM increases the risk of developing heart failure, for which no cure is available, and the risk of stroke and sudden cardiac death.

These findings will not only help patients understand the cause of their DCM symptoms, but also help to screen family members who might be at risk of developing the condition. Early identification of those at risk allows early intervention with medications that reduce workload on the heart and help prevent the changes in heart muscle, called remodeling, that lead to heart failure.

As DCM progresses, remodeling of the heart tissue makes the heart more prone to disturbances in the normal heart rhythm that can lead to stroke, heart attack and sudden death. “One of the added values to knowing that you are at risk for developing DCM is that we can do prophylactic screening so that silent arrhythmias are picked up before they become harmful,” said Christine Seidman. “The discovery is immediately translatable into clinical practice to provide patients with gene-based diagnosis.” The Partner’s Laboratory for Molecular Medicine, an HMS affiliate, has incorporated TTN analyses.

The Seidmans and others had previously linked other gene mutations to about 20 to 30 percent of idiopathic DCM cases — and, with more success, to a related disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. They had examined almost all of the genes linked to muscle units known as sarcomeres, but saved the biggest for last: TTN, which encodes the protein titin. At approximately 33,000 amino acids, titin is the largest human protein.

“Titin was a missing link,” said Christine Seidman. “A very large missing link.”

The Seidmans’ collaborated with researchers from the Imperial College (London) and the University of Washington. Traditional sequencing methods had previously found only a few TTN variants in patients with DCM because complete, accurate sequencing was too expensive.

Using next generation sequencing tools that substantially reduce the cost per base (the TTN sequence contains 100,000 bases) by orders of magnitude over earlier standards, the Seidmans were able to perform comprehensive screening for TTN mutations for the first time. They analyzed TTN in 312 DCM patients, 231 HCM patients, and 249 individuals with no disease.

Of the many mutations identified, 72 make the titin protein shorter.

Called TTN truncating variants, these specific mutations appeared almost exclusively in patients with DCM. “Our hypothesis is that any variant that shortens titin is going to cause DCM, which will lead to heart failure by the same mechanism,” said Jonathan Seidman.

To identify the pathological mechanism, the Seidmans plan to model a handful of TTN truncating mutations in mice.

One concern in the search for disease causing genes is that, while there will be many gene variants discovered, only a few will cause disease. This is particularly true for missense mutations that cause single nucleotide changes — changes that substitute a single amino acid within the protein.

“We often don’t know if a missense mutation significantly impacts a protein’s function, until we model it and study its effects,” said Jonathan Seidman.

However, in the case of truncating mutations, “it’s the converse,” he continued. “We don’t have to model all of those different mutations that truncate titin, becuase they all foreshorten the protein. We can pick a few representative ones and expect that they will reveal a common mechanism.”

A better understanding of the mechanism may lead to better and more direct therapies for treatment and prevention of DCM.

This research was funded by Howard Hughes Medical Institute; National Institutes of Health; Leducq Foundation; American Heart Association and Muscular Dystrophy Association; and the UK National Institute for Health Research Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit.

Be the first to comment on "Mutations in TTN Gene Cause Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy (DCM)"