Acid rain is primarily caused by sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere.

The National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program stated a decrease in acid rain in a report that was presented to Congress. The report states that sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions have continued to decline and are lower than the 2009 levels. Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the atmosphere are the primary causes of acid rain.

Measurable improvements in air quality and visibility, human health, and water quality in many acid-sensitive lakes and streams, have been achieved through emissions reductions from electric generating power plants and resulting decreases in acid rain. These are some of the key findings in a report to Congress by the National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program, a cooperative federal program.

The report shows that since the establishment of the Acid Rain Program, under Title IV of the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, there have been substantial reductions in sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions from power plants that use fossil fuels like coal, gas, and oil, which are known to be the primary causes of acid rain. As of 2009, emissions of SO2 and NOx declined by about two-thirds relative to levels in the 1990s. These emissions levels declined even further in 2010, according to recent data compiled by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Because emission reductions result in fewer fine particles and lower ozone concentrations in the air, in 2010 there were thousands fewer premature human deaths, hospital admissions, and emergency room visits annually leading to estimated human health benefits valued at $170 to $430 billion per year.

“The SO2 [portion of the] program includes the use of a creative emissions cap-and-trade program that combines the best of American science, government, and market-driven innovation,” said Dr. John P. Holdren, director of Office of Science and Technology Policy and assistant to the President for science and technology.

Despite these emission reductions, the report also indicates that full recovery from the effects of acid rain is not likely for many sensitive forests and aquatic ecosystems. For example, in the Adirondack Mountains of New York, an especially sensitive region, 30 percent of the lakes were receiving acid rain during 2006-08 in excess of the level needed to prevent harm.

Based on models which analyze various emission scenarios, the report concludes that beyond current SO2 and NOx emission levels, future emission reductions would likely promote additional and more widespread recovery as well as to prevent further acidification in some U.S. regions.

“The principal message of this report is that the Acid Rain Program has worked. The emissions that form acid rain have declined and some U.S. areas are beginning to recover,” said Doug Burns, lead author and director of the NAPAP and also a U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist. “However, some sensitive ecosystems are still receiving levels of acid rain that exceed what is needed for full and widespread recovery. We have every reason to believe that recovery will continue with further decreases in emissions which is why further emission reductions would be beneficial.”

The NAPAP reports to Congress on the latest scientific information and analysis concerning the costs, benefits, and environmental effectiveness of the Acid Rain Program, which was established by the Clean Air Act Amendments to reduce the primary sources of acid rain. Member agencies include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Departments of Energy, Interior and Agriculture, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

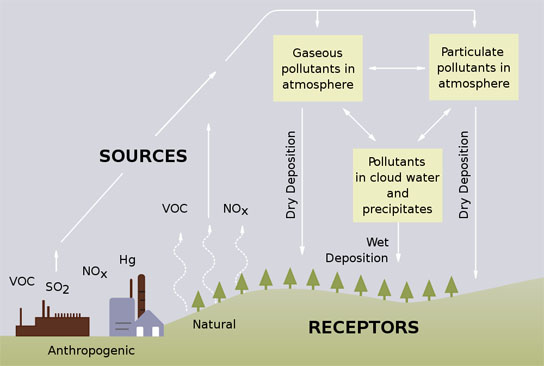

Acid rain occurs when emissions of SO2 and NOx react in the atmosphere with water, oxygen, and oxidants to form acidic compounds. These emissions may be transported hundreds of miles away from their emitting sources, and have the potential to impact large areas and populations.

Together these acidic compounds can damage human health, and in addition to degrading air quality and visibility, can cause further environmental damage, including acidification of lakes and streams, harm to sensitive forests and coastal ecosystems, and accelerate the decay of building materials. Adverse ecological impacts from acid rain include reductions in biodiversity, an increased risk of damaging forest fires, and increased susceptibility of trees to pests, disease, and winter temperatures.

The report also highlights the need for better information including the costs and benefits to ecosystems from emission reductions, consideration of the role of climate change, and the interactions of multiple pollutants.

Be the first to comment on "National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program Reports Decreases in Acid Rain"