This is an artist’s rendering of A. burmitina feeding on eudicot flowers. Credit: Illustration by Ding-hau Yang

A new study co-led by researchers in the U.S. and China has pushed back the first-known physical evidence of insect flower pollination to 99 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous period.

The revelation is based upon a tumbling flower beetle with pollen on its legs discovered preserved in amber deep inside a mine in northern Myanmar. The fossil comes from the same amber deposit as the first ammonite discovered in amber, which was reported by the same research group earlier this year.

The report of the new fossil was published today (November 11, 2019) in the journal of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The fossil, which contains both the beetle and pollen grains, pushes back the earliest documented instance of insect pollination to a time when pterodactyls still roamed the skies — or about 50 million years earlier than previously thought.

This is A. burmitina in amber. The 99-million-year-old fossil, recovered from a mine in northern Myanmar, also contains 62 pollen grains from a eudicot flower. It is the earliest known physical evidence of insect pollination. Credit: Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology

The study’s U.S. co-author is David Dilcher, an emeritus professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Earth and Atmospheric Science and a research affiliate of the Indiana Geological and Water Survey. As a paleobotanist studying the earliest flowering plants on Earth, Dilcher has conducted research on the process of amber fossilization.

The co-lead author on the study is Bo Wang, an amber fossil expert at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, where the specimen was procured and analyzed.

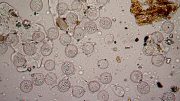

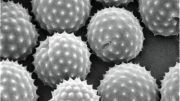

According to Dilcher, who provided a morphological review of the 62 grains of pollen in the amber, the shape, and structure of the pollen show it evolved to spread through contact with insects. These features include the pollen’s size, “ornamentation” and clumping ability.

The grains also likely originated from a flower species in the group eudicots, one of the most common types of flowering plant species, he said.

This is a close up of A. burmitina in amber. The fossil also contains 62 pollen grains from a eudicot flower, which indicates the insect’s role as a pollinator. Credit: Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology

The pollen was not easy to find. The powdery substance was revealed hidden in the insect’s body hairs under a confocal laser microscopy. The analysis took advantage of the fact that pollen grains glow under fluorescence light, contrasting strongly with the darkness of the insect’s shell.

The insect in the amber is a newly discovered species of beetle, which the study’s authors named Angimordella burmitina. Its role as a pollinator was determined based on several specialized physical structures, including body shape and pollen-feeding mouthparts. These structures were revealed through an imaging method called X-ray microcomputed tomography, or micro-CT.

“It’s exceedingly rare to find a specimen where both the insect and the pollen are preserved in a single fossil,” said Dilcher. “Aside from the significance as earliest known direct evidence of insect pollination of flowering plants, this specimen perfectly illustrates the cooperative evolution of plants and animals during this time period, during which a true exposition of flowering plants occurred.”

Prior to this study, the earliest physical evidence of insect pollination of flowering plants came from Middle Eocene. The age of the new fossil was determined based on the age of other known fossils in the same location as the fossilized beetle’s discovery.

###

Reference: “Pollination of Cretaceous flowers” by Tong Bao, Bo Wang, Jianguo Li and David Dilcher, 11 November 2019, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1916186116

Other authors on the study were Tong Bao and Jianguo Li of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology. Boa is also affiliated with the Institute of Geosciences and Meteorology at the University of Bonn in Germany.

This work was supported in part by the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Be the first to comment on "New Fossil Discovery Pushes Back Evidence of Insect Pollination to a Time When Pterodactyls Still Roamed the Skies"