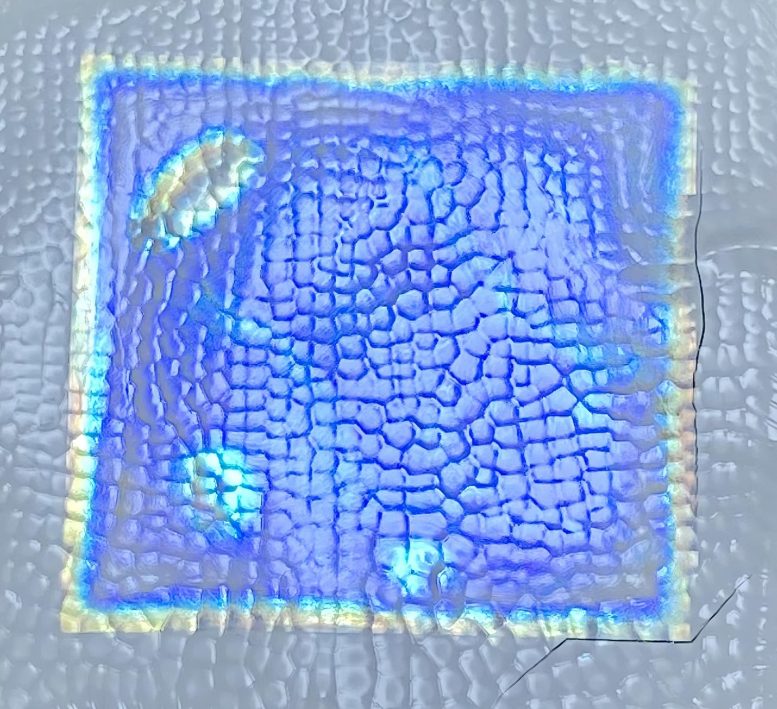

A colorful, textured bi-layer film made from plant-based materials cools down when it’s in the sun. Credit: Qingchen Shen

The cool breeze of an air conditioner can provide much-needed relief in scorching heat, but these units consume substantial amounts of energy and can release potent greenhouse gases. Now, scientists have introduced an environmentally friendly alternative — a plant-based film that cools down when exposed to sunlight and comes in a variety of textures and vivid, iridescent colors. This material has the potential to cool down buildings, vehicles, and other structures without the need for external power in the future.

The researchers recently presented their findings at the spring meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS).

“To make materials that remain cooler than the air around them during the day, you need something that reflects a lot of solar light and doesn’t absorb it, which would transform energy from the light into heat,” says Silvia Vignolini, Ph.D., the project’s principal investigator. “There are only a few materials that have this property, and adding color pigments would typically undo their cooling effects,” Vignolini adds.

Passive daytime radiative cooling (PDRC) is the ability of a surface to emit its own heat into space without it being absorbed by the air or atmosphere. The result is a surface that, without using any electrical power, can become several degrees colder than the air around it. When used on buildings or other structures, materials that promote this effect can help limit the use of air conditioning and other power-intensive cooling methods.

Some paints and films currently in development can achieve PDRC, but most of them are white or have a mirrored finish, says Qingchen Shen, Ph.D., who is presenting the work at the meeting. Both Vignolini and Shen are at Cambridge University (U.K.). But a building owner who wanted to use a blue-colored PDRC paint would be out of luck — colored pigments, by definition, absorb specific wavelengths of sunlight and only reflect the colors we see, causing undesirable warming effects in the process.

But there’s a way to achieve color without the use of pigments. Soap bubbles, for example, show a prism of different colors on their surfaces. These colors result from the way light interacts with differing thicknesses of the bubble’s film, a phenomenon called structural color. Part of Vignolini’s research focuses on identifying the causes behind different types of structural colors in nature. In one case, her group found that cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), which are derived from the cellulose found in plants, could be made into iridescent, colorful films without any added pigment.

As it turns out, cellulose is also one of the few naturally occurring materials that can promote PDRC. Vignolini learned this after hearing a talk from the first researchers to have created a cooling film material. “I thought wow, this is really amazing, and I never really thought cellulose could do this.”

In recent work, Shen and Vignolini layered colorful CNC materials with a white-colored material made from ethyl cellulose, producing a colorful bi-layered PDRC film. They made films with vibrant blue, green, and red colors that, when placed under sunlight, were on average about 7 F cooler than the surrounding air. A square meter of the film generated over 120 Watts of cooling power, rivaling many types of residential air conditioners. The most challenging aspect of this research, Shen says, was finding a way to make the two layers stick together — on their own, the CNC films were brittle, and the ethyl cellulose layer had to be plasma-treated to get good adhesion. The result, however, was films that were robust and could be prepared several meters at a time in a standard manufacturing line.

Since creating these first films, the researchers have been improving their aesthetic appearance. Using a method modified from approaches previously explored by the group, they’re making cellulose-based cooling films that are glittery and colorful. They’ve also adjusted the ethyl cellulose film to have different textures, like the differences between types of wood finishes used in architecture and interior design, says Shen. These changes would give people more options when incorporating PDRC effects in their homes, businesses, cars, and other structures.

The researchers now plan to find ways they can make their films even more functional. According to Shen, CNC materials can be used as sensors to detect environmental pollutants or weather changes, which could be useful if combined with the cooling power of their CNC-ethyl cellulose films. For example, a cobalt-colored PDRC on a building façade in a car-dense, urban area could someday keep the building cool and incorporate detectors that would alert officials to higher levels of smog-causing molecules in the air.

Meeting: ACS Spring 2023

The researchers acknowledge support and funding from Purdue University, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the European Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the European Union and Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Great. And these films deteriorate in about 6 days in weather.

I find this very interesting but passive cooling systems are not a new thing. Circulating air through underground pipes gives access to 55°Fahrenheit temperatures during any time period and only requires the movement of the air by a perhaps solar powered fan. By creating a central masonry structure with the same pipes and using the same fan system, you can get heat from the sun shining on the structure and store it through envelope type framing of the building. This type of thing has been operating in the rather demanding environment of the Midwest for decades at an annual cost of $200.