Strawberry tongue seen in scarlet fever. Credit: Martin Kronawitter, CC BY-SA 2.5

A University of Queensland-led team of international researchers says supercharged “clones” of the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes are to blame for the resurgence of the disease, which has caused high death rates for centuries.

UQ’s Dr. Stephan Brouwer said health authorities globally were surprised when an epidemic was detected in Asian countries in 2011.

“The disease had mostly dissipated by the 1940s,” Dr. Brouwer said.

“Like the virus that causes COVID-19, Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria are usually spread by people coughing or sneezing, with symptoms including a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, and a characteristic scarlet-colored, red rash.

“Scarlet fever commonly affects children, typically aged between two and 10 years.

“After 2011, the global reach of the pandemic became evident with reports of a second outbreak in the UK, beginning in 2014, and we’ve now discovered outbreak isolates here in Australia.

“This global re-emergence of scarlet fever has caused a more than five-fold increase in disease rate and more than 600,000 cases around the world.”

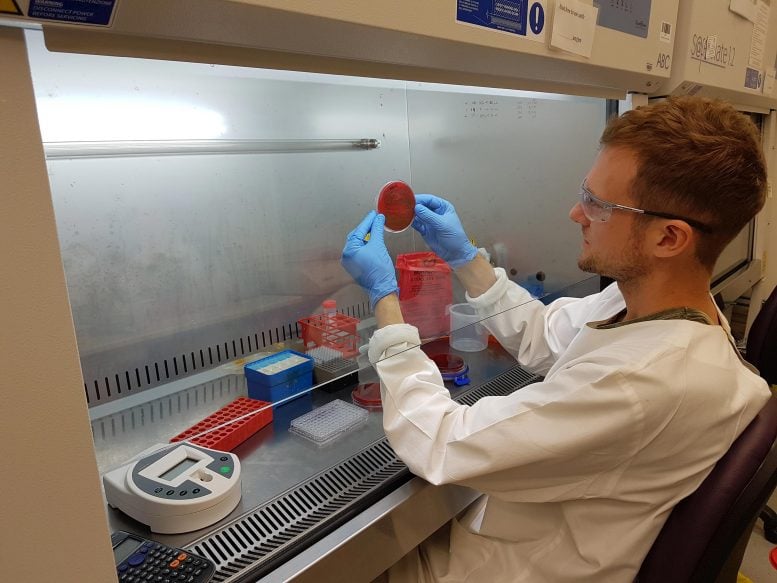

The University of Queensland’s Dr. Stephan Brouwer is helping reveal why scarlet fever is making a comeback. Credit: The University of Queensland

Co-author Professor Mark Walker and the team found a variety of Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria that had acquired “superantigen” toxins, forming new clones.

“The toxins would have been transferred into the bacterium when it was infected by viruses that carried the toxin genes,” Professor Walker said. “We’ve shown that these acquired toxins allow Streptococcus pyogenes to better colonize its host, which likely allows it to out-compete other strains.

“These supercharged bacterial clones have been causing our modern scarlet fever outbreaks.

“The research team then removed the toxin genes from the clones causing scarlet fever, and these modified ‘knock-out’ clones were found to be less able to colonize in an animal model of infection.”

For the time being, scarlet fever outbreaks have been dampened, largely due to public health policy measures introduced to control COVID-19.

“This year COVID-19 social distancing has kept scarlet fever outbreaks in check for now,” Professor Walker said. “And the disease’s main target — children — have been at school less and also spending far less time in other large groups.

“But when social distancing eventually is relaxed, scarlet fever is likely to come back. We need to continue this research to improve diagnosis and to better manage these epidemics.

“Just like COVID-19, ultimately a vaccine will be critical for eradicating scarlet fever — one of history’s most pervasive and deadly childhood diseases.”

Reference: “Prophage exotoxins enhance colonization fitness in epidemic scarlet fever-causing Streptococcus pyogenes” by Stephan Brouwer, Timothy C. Barnett, Diane Ly, Katherine J. Kasper, David M. P. De Oliveira, Tania Rivera-Hernandez, Amanda J. Cork, Liam McIntyre, Magnus G. Jespersen, Johanna Richter, Benjamin L. Schulz, Gordon Dougan, Victor Nizet, Kwok-Yung Yuen, Yuanhai You, John K. McCormick, Martina L. Sanderson-Smith, Mark R. Davies and Mark J. Walker, 6 October 2020, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-18700-5

This research was a collaboration between UQ, Telethon Kids Institute, University of Wollongong, Western University (Canada), the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (University of Melbourne), University of Cambridge, University of California San Diego, The University of Hong Kong and the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever is a disease resulting from a group A streptococcus (group A strep) infection, also known as Streptococcus pyogenes. The signs and symptoms include a sore throat, fever, headaches, swollen lymph nodes, and a characteristic rash. The rash is red and feels like sandpaper and the tongue may be red and bumpy. It most commonly affects children between five and 15 years of age.

Scarlet fever affects a small number of people who have strep throat or streptococcal skin infections. The bacteria are usually spread by people coughing or sneezing. It can also be spread when a person touches an object that has the bacteria on it and then touches their mouth or nose. The characteristic rash is due to the erythrogenic toxin, a substance produced by some types of bacterium. The diagnosis is typically confirmed by culturing the throat.

There is no vaccine. Prevention is by frequent handwashing, not sharing personal items, and staying away from other people when sick. The disease is treatable with antibiotics, which prevent most complications. Outcomes with scarlet fever are typically good if treated. Long-term complications as a result of scarlet fever include kidney disease, rheumatic heart disease, and arthritis. In the early 20th century, before antibiotics were available, it was a leading cause of death in children.

Be the first to comment on "Supercharged Bacterial “Clones” Spark Scarlet Fever’s Global Re-emergence"