Viruses are intracellular parasites that cause disease by infecting the cells in the body and, in a study published today in Nature Microbiology, researchers at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine showed how a common virus hijacks a host cell’s protein to help assemble new viruses before they are released. The findings increase our understanding of how viruses reproduce in the body and could lead to new therapeutics.

While most research into viral infections has focused on mechanisms viruses use to enter cells, less is known about the late steps in infection. The new findings were identified in reovirus, a common virus that is normally harmless but has recently been implicated as a potential cause of celiac disease.

“Our work provides compelling evidence that reoviruses, and perhaps additional distantly related viruses, require a specialized protein-folding machine expressed in cells to replicate,” said Terence Dermody, M.D., chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Pitt’s School of Medicine, physician-in-chief and scientific director at Children’s Hospital, and the senior author on the study. “This is a pretty remarkable finding because viruses are in large part made of complex protein building blocks and we know little about how these blocks are assembled.”

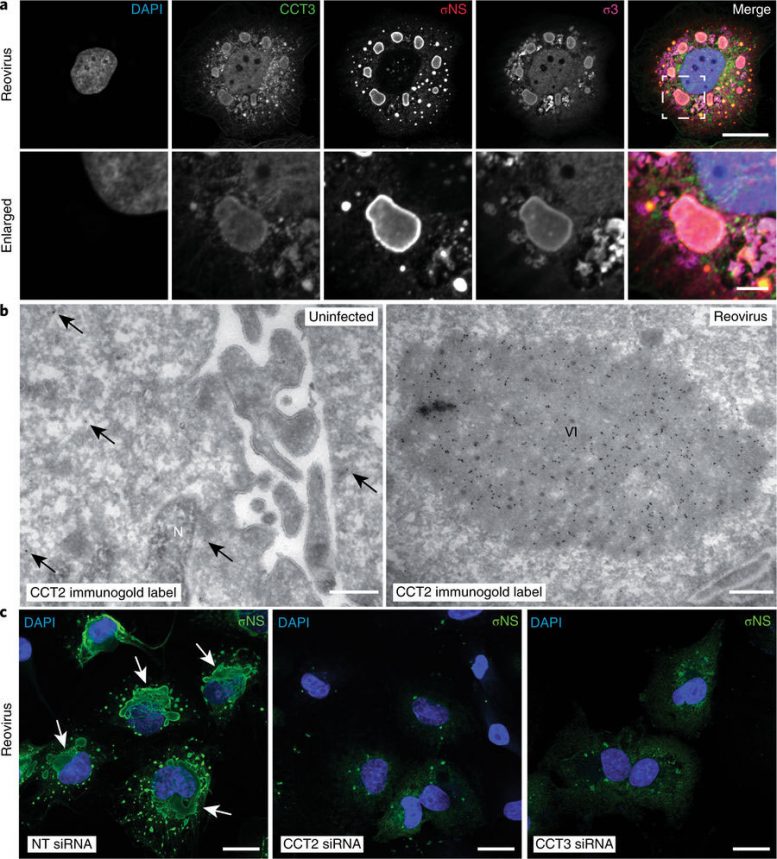

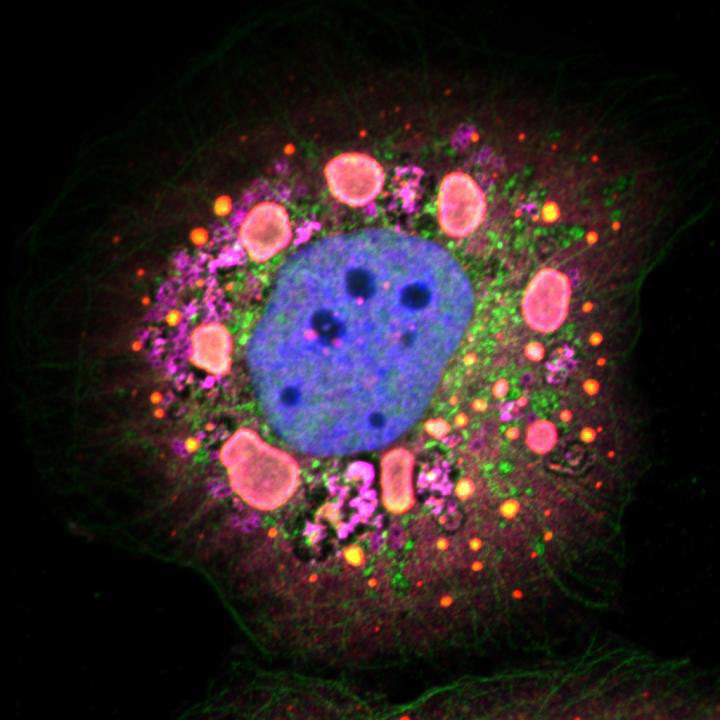

Fig. 3: TRiC redistributes to viral inclusions and is required for inclusion morphogenesis. a, Confocal immunofluorescence images of T3D reovirus-infected HBMECs (MOI of 100 PFU per cell, 24 h post infection) stained with DAPI (blue) and antibodies specific for CCT3 (green), σNS (red) and σ3 (magenta). Viral inclusions are identifiable by σNS staining. Enlarged images correspond to the region indicated by the white dashed box in the merged image. Scale bars, 20 µm and 4 µm in full-size and enlarged images, respectively. b, Tokuyasu cryosections of uninfected or T1L reovirus-infected (MOI of 1 PFU per cell, 20 h post infection) HBMECs immunogold labeled for CCT2. Scale bars, 500 nm. Arrows indicate gold particles observed in uninfected cells. VI, viral inclusion; N, nucleus. c, confocal immunofluorescence images of HBMECs transfected with NT or TRiC subunit-specific siRNAs, infected with T1L reovirus (MOI of 100 PFU per cell, 24 h post infection) and stained with DAPI (blue) and a σNS-specific antiserum (green). Scale bars, 20 µm. Large, globular inclusions are marked by white arrows. Images are representative of three independent experiments conducted with similar results. Jonathan J. Knowlton, et al., Nature Microbiology (2018) doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0122-x

Folding proteins in the right way is crucial to their function. “Think of an unfolded protein like a plain sheet of paper: Rather unremarkable by itself, but capable of performing sophisticated functions when folded in a certain way, such as into an airplane. Similarly, proteins need to fold into specific shapes to work correctly,” said Jonathan Knowlton, the first author of the study and a researcher in Dermody’s lab.

By screening a large number of proteins in lab-grown cells, the researchers discovered that reovirus hijacks a chaperone protein – a machine that folds other proteins – called TRiC, that is present in every cell. In the case of reovirus, TRiC folds a major component of the protein shell that forms the outer coat of the virus, which is required for it to exit the cell and infect other healthy cells. When TRiC is disrupted, the outer coat cannot form and the cycle of viral replication is broken.

This study sheds light on the poorly understood process by which viral proteins fold and assemble to form new particles. The researchers are now studying whether other viruses use this pathway to reproduce, identifying the exact steps in the folding process enabled by TRiC and looking for molecules that inhibit the process, which could be developed as therapies.

In addition, this research contributes to an understanding of how the protein-folding machinery functions inside cells and may explain the manifestations of protein-misfolding diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s.

Reference: “The TRiC chaperonin controls reovirus replication through outer-capsid folding” by Jonathan J. Knowlton, Isabel Fernández de Castro, Alison W. Ashbrook, Daniel R. Gestaut, Paula F. Zamora, Joshua A. Bauer, J. Craig Forrest, Judith Frydman, Cristina Risco and Terence S. Dermody, 12 March 2018, Nature Microbiology.

DOI: 10.1038/s41564-018-0122-x

Be the first to comment on "University Biologists Identify Key Step in Viral Replication"