Researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas have found that age-related memory decline involves complex neural changes, challenging existing theories and underscoring the need for nuanced research into cognitive aging.

Scientists have discovered that the brain’s aging process is more complex than previously thought, with different mechanisms affecting how memory and cognitive functions decline.

Researchers from The University of Texas at Dallas Center for Vital Longevity (CVL) have discovered that brain correlates of age-related memory decline are more complicated than previously believed, a finding that could affect efforts to preserve cognitive health in older people.

Dr. Michael Rugg, CVL director and professor of psychology in the School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, is the senior author of a study, published online on November 30 and in the January 24 print edition of The Journal of Neuroscience, that found that age-related neural dedifferentiation, marked by a decline in the functional specialization of different brain regions, is driven by multiple mechanisms.

As people age — even in good health — the brain becomes less precise in how different classes of visual information are represented in the visual cortex. This reduction in neural selectivity, or dedifferentiation, is linked to worsening memory performance.

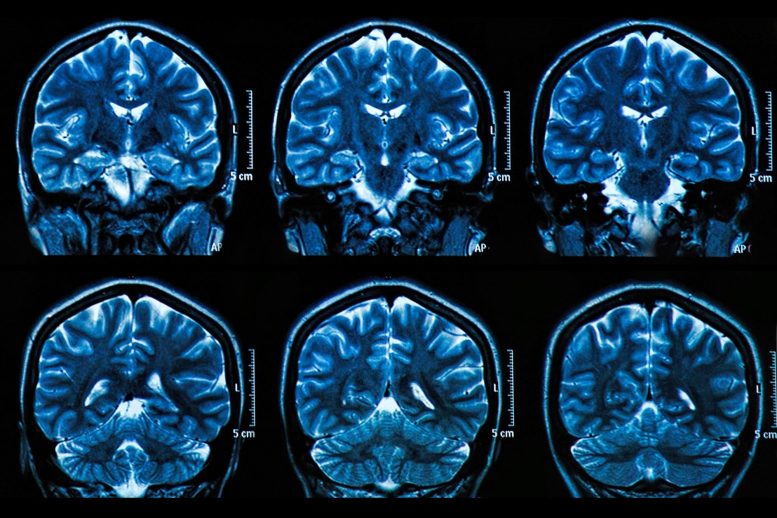

Using functional MRI (fMRI), the researchers examined the brain activity patterns of participants as they viewed images that belonged to broad categories of panoramic scenes and objects. Some of the images were repeated, thus allowing measurement of the brain’s activity patterns elicited by image categories, as well as by individual stimulus items. The participants included groups of healthy young and older adults — 24 men and women with an average age of 22 years, and 24 with an average age of 69 years.

Sabina Srokova PhD’22 and Dr. Michael Rugg, director of the Center for Vital Longevity, published a study in The Journal of Neuroscience examining neural dedifferentiation, age and memory abilities. Credit: Center for Vital Longevity / The University of Texas at Dallas

“At the category level, as we expected, we found that the older group showed reduced selectivity for scenes compared to the younger group, but not for objects,” Rugg said. “But when we looked at individual items, selectivity for both scenes and objects were reduced in the older group. This implies that the mechanisms driving dedifferentiation at the single item level are not the same as those at the category level. We had, to this point, assumed they were one and the same mechanism.”

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all theory of age-related neural dedifferentiation. This has important implications for how we understand and investigate age differences in neural selectivity.”

— Dr. Michael Rugg, the Distinguished Chair in Behavioral and Brain Sciences

The implication, Rugg said, is that knowing how selective an individual’s brain is for categories does not predict how selective the brain will be for individual items.

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all theory of age-related neural dedifferentiation,” said Rugg, who is also the Distinguished Chair in Behavioral and Brain Sciences. “This has important implications for how we understand and investigate age differences in neural selectivity, some measures of which are predictive of memory performance. Moving forward, we’re going to have to be more cautious in how we generalize from category-level findings to what’s happening more broadly in the brain as people grow older.”

Corresponding author Sabina Srokova PhD’22, a former student of Rugg’s who is now a research associate at the University of Arizona, said the findings suggest at least two independent factors drive the reduction in selectivity in older adults.

“We know that the neural mechanisms underlying category-level selectivity are robustly related to memory success across the adult lifespan,” Srokova said. “However, the factors that contribute to the relationship between neural selectivity, age, and memory abilities remain unknown.

“Now that we believe different neural mechanisms are at work in these two contexts, it’s crucial that we continue to study them separately.”

Researchers will next examine the mechanisms that contribute to age-related declines in category-level selectivity using simultaneous recording of eye movements during fMRI scanning.

Reference: “Dissociative Effects of Age on Neural Differentiation at the Category and Item Levels” by Sabina Srokova, Ayse N. Z. Aktas, Joshua D. Koen and Michael D. Rugg, 23 January 2024, Journal of Neuroscience.

DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0959-23.2023

Additional study authors include Dr. Joshua D. Koen, a former postdoctoral fellow in Rugg’s functional Neuroimaging of Memory laboratory, and lab research assistant Ayse Aktas.

The work was funded by the National Institute on Aging, a component of the National Institutes of Health (R56AG068149 and RF1AG039103), and by the nonprofit organization BvB Dallas.

First writing of my early lay findings of it to JACI and The Lancet in 2011, at age sixty-seven (in-vain; not published), I’ve written of this many times since: Dr. Arthur F. Coca’s kind of nearly subclinical non-IgE-mediated food (minimally) allergy reactions (by 1935) can cause an acidic blood condition which the poorly nourished body may not be able to correct. With obesity and so-called “male-pattern-baldness” being the first and second most obvious symptoms of long-term disease progress (months to decades; highly individual), where the acidic blood flow is the greatest the most damage will occur. As we age and our interests change (e.g., increasing disability, minimally) the greatest blood flow in our brains will change from one region or another to a new region or another. There, I believe, is the “…one-size-fits-all theory of age-related neural dedifferentiation.” that, too-typically, most professional researchers have yet to learn.