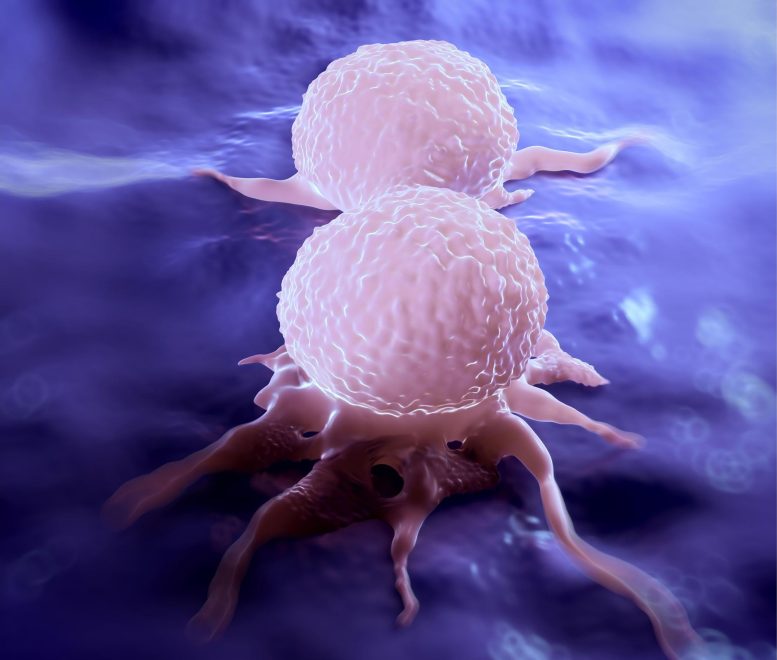

Breast cancer is a type of cancer that develops in the breast tissue. It is one of the most common types of cancer among women worldwide. Breast cancer can occur in both men and women, however, it is rare in men. Early signs and symptoms of breast cancer include a lump or thickening in the breast tissue, changes in the shape or size of the breast, and changes in the skin of the breast, such as dimpling or redness.

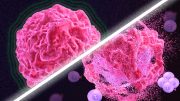

Surviving chemotherapy activates a program of immune checkpoints that protect breast cancer cells from various forms of attack by the immune system.

Cancer therapies have made significant progress, and as a result, many forms of breast cancer have a high chance of being treated successfully, particularly when detected early.

However, the most challenging cases, those that cannot be treated with hormone or targeted therapies and do not respond to chemotherapy, are still the most deadly and difficult to treat. Tulane University researchers have, for the first time, uncovered how these cancers persist after chemotherapy and why they do not respond well to immunotherapies, which aim to eliminate remaining tumor cells by activating the immune system.

The process of surviving chemotherapy triggers a program of immune checkpoints that shield breast cancer cells from different lines of attack by the immune system. It creates a “whack-a-mole” problem for immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors that may kill tumor cells expressing one checkpoint but not others that have multiple checkpoints, according to a new study published in the journal Nature Cancer.

“Breast cancers don’t respond well to immune checkpoint inhibitors, but it has never really been understood why,” said corresponding author James Jackson, Ph.D., associate professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Tulane University School of Medicine. “We found that they avoid immune clearance by expressing a complex, redundant program of checkpoint genes and immune modulatory genes. The tumor completely changes after chemotherapy treatment into this thing that is essentially built to block the immune system.”

Researchers studied the process in mouse and human breast tumors and identified 16 immune checkpoint genes that encode proteins designed to inactivate cancer-killing T-cells.

“We’re among the first to actually study the tumor that survives post-chemotherapy, which is called the residual disease, to see what kind of immunotherapy targets are expressed,” said the study’s first author Ashkan Shahbandi, an MD/Ph.D. student in Jackson’s lab.

The tumors that respond the worst to chemotherapy enter a state of dormancy – called cellular senescence – instead of dying after treatment. Researchers found two major populations of senescent tumor cells, each expressing different immune checkpoints activated by specific signaling pathways. They showed the expression of immune evasion programs in tumor cells required both chemotherapy to induce a senescent state and signals from non-tumor cells.

They tested a combination of drugs aimed at these different immune checkpoints. While response could be improved, these strategies failed to fully eradicate the majority of tumors.

“Our findings reveal the challenge of eliminating residual disease populated by senescent cells that activate complex immune inhibitory programs,” Jackson said. “Breast cancer patients will need rational, personalized strategies that target the specific checkpoints induced by the chemotherapy treatment.”

Reference: “Breast cancer cells survive chemotherapy by activating targetable immune-modulatory programs characterized by PD-L1 or CD80” by Ashkan Shahbandi, Fang-Yen Chiu, Nathan A. Ungerleider, Raegan Kvadas, Zeinab Mheidly, Meijuan J. S. Sun, Di Tian, Daniel A. Waizman, Ashlyn Y. Anderson, Heather L. Machado, Zachary F. Pursell, Sonia G. Rao and James G. Jackson, 8 December 2022, Nature Cancer.

DOI: 10.1038/s43018-022-00466-y

The study was funded by the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program, the National Cancer Institute, and the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Be the first to comment on "Why Doesn’t Immunotherapy Work for All Breast Cancers?"