Chad Ostrander, lead author of the study, preparing a short sediment core collected from the East Gotland Basin during the investigation. Credit: Colleen Hansel, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

New research by scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and other institutions reveals that human activities have contributed significantly to the presence of toxic thallium in the Baltic Sea, accounting for between 20% and 60% of the total thallium pollution over the last 80 years.

Currently, the amount of thallium (element symbol TI), which is considered the most toxic metal for mammals, remains low in Baltic seawater. However, the research suggests that the amount of thallium could increase due to further anthropogenic, or human-induced, activities, or due to natural or human re-oxygenation of the Baltic that could make the sea less sulfide-rich. Much of the thallium in the Baltic Sea, the largest human-induced hypoxic area on Earth, accumulates in the sediment thanks to abundant sulfide minerals.

“Anthropogenic activities release considerable amounts of toxic thallium annually. This study evidences an increase in the amount of thallium delivered by anthropogenic sources to the Baltic Sea since approximately 1947,” according to the study, recently published in Environmental Science & Technology.

“Humans are releasing a lot of thallium into the Baltic Sea, and people should be made aware of that. If this continues – or if we further change the chemistry of the Baltic Sea in the future or if it naturally changes – then more thallium could accumulate. That would be of concern because of its toxicity,” said Chadlin Ostrander lead author of the article, which he conducted as a postdoctoral investigator in WHOI’s Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry. Currently, he is an assistant professor in the Department of Geology & Geophysics at the University of Utah.

Study Methods and Historical Context

For the study, the researchers set out to better understand how thallium and its two stable isotopes 203Tl and 205Tl are cycled in the Baltic Sea. To discern modern thallium cycling, concentration, and isotope ratio data were collected from seawater and shallow sediment core samples. To reconstruct thallium cycling further back in time, the researchers supplemented their short core samples with a longer sediment core that had been collected earlier near one of the deepest parts of the sea. They found Baltic seawater to be considerably more enriched in 205Tl than predicted. This enrichment started around 1940 to 1947 according to the longer sediment core.

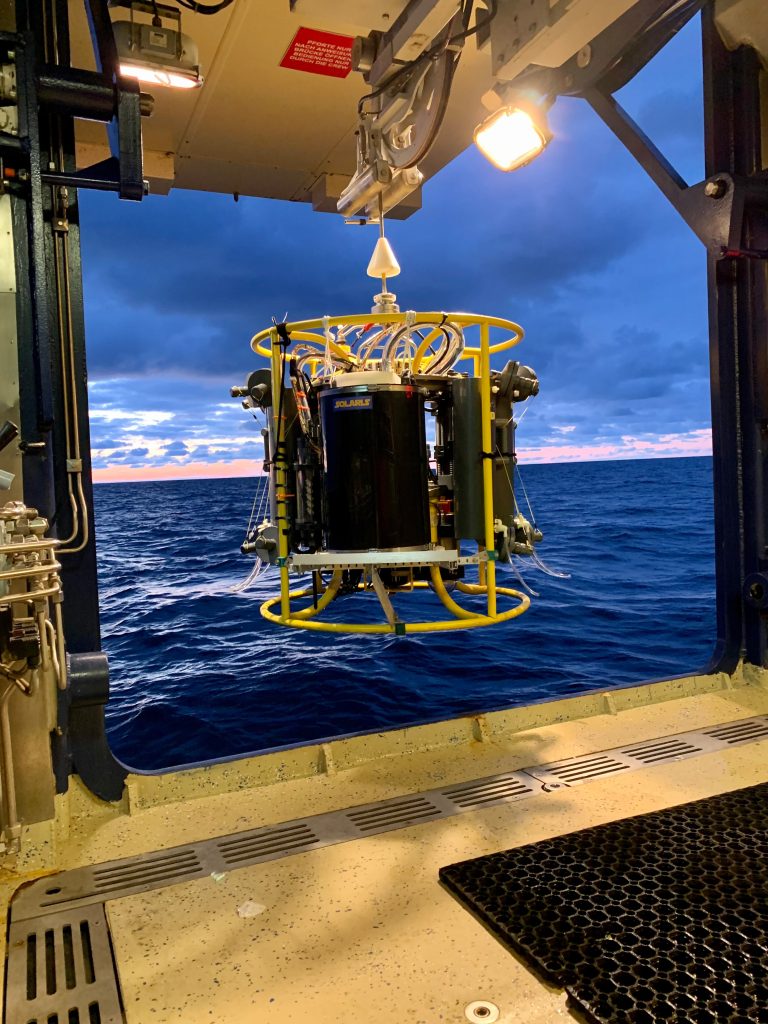

An early-morning cast, to collect water samples and make in-situ measurements, during the Baltic Sea investigation. Credit: Colleen Hansel, ©Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

It would be “highly coincidental” if the 205Tl increase was not associated with the “nearly contemporaneous trends linked to anthropogenic activities,” the article states. Though the exact sources of the thallium increase are not yet known, the article indicates that regional cement production, which was enhanced after the end of World War II, may play an important role, with other possible sources including coal combustion and the roasting of pyrite, an iron sulfide.

Regional Impact and Environmental Concerns

“For me, the most important aspect of the study is that we basically discovered that large portions – if not most – of the Baltic Sea are contaminated with the toxic metal thallium from human activities surrounding the basin,” said co-author Sune Nielsen, an adjunct scientist in WHOI’s Department of Geology & Geophysics. “As far as I am aware, this constitutes the geographically most extensive area of thallium contamination ever documented. It has long been known that the Baltic Sea has been strongly affected by anthropogenic activity, not least via the increasingly persistent loss of oxygen that has led to big losses for the fishing industry over the last several decades. As a Danish national, I follow the (bad) news about the Baltic in the Danish media, and our finding just adds another dimension to the already poor conditions in the basin for marine life. While thallium contamination may not be the most immediate concern for the Baltic Sea ecosystem, there is no doubt in my mind that it adds to the urgency of needing to do something to bring the Baltic Sea back to a state where humans and marine life can co-exist naturally.”

“Our data strengthens evidence that the removal of thallium from seawater and storage within sediments is tightly controlled by the absence of oxygen and presence of sulfide,” said co-author Colleen Hansel, a senior scientist in WHOI’s Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry. “It is therefore concerning that recent movements to ‘solve the anoxia problem’ in the Baltic Sea involve pumping oxygen into the bottom waters. This oxygenation of the Baltic will likely lead to the release of thallium, as well as other sulfide-hosted metals like mercury, into the overlying seawater where they could bioaccumulate to toxic levels in fish. We predict, based on activities in the region, that the source of the thallium pollution is historic cement production in the region. As cement production continues to rise globally, this research could serve to caution manufacturers about the need to mitigate the potential downstream effects of cement kiln dust on surrounding aquatic and marine ecosystems. This study highlights the utility of isotopes in identifying sources of pollutants to marine ecosystems, which is difficult to disentangle with concentration data alone.”

Reference: “Anthropogenic Forcing of the Baltic Sea Thallium Cycle” by Chadlin M. Ostrander, Yunchao Shu, Sune G. Nielsen, Olaf Dellwig, Jerzy Blusztajn, Heide N. Schulz-Vogt, Vera Hübner and Colleen M. Hansel, 2 May 2024, Environmental Science & Technology.

DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.4c01487

Funding for this research was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation and by the Leibniz Association.

Be the first to comment on "Decades of Damage: Humans Are Contaminating the Baltic Sea With Toxic Metals"