Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks its own healthy tissues and organs. This results in inflammation and damage to various parts of the body, including the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, lungs, brain, and blood cells.

Targeting iron metabolism in immune system cells could be a potential new approach for treating systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), the most prevalent form of the chronic autoimmune disease lupus.

Researchers from Vanderbilt University Medical Center recently published their findings in the journal Science Immunology, revealing that by blocking an iron uptake receptor, disease pathology is reduced and the activity of anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells is increased in a mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Lupus, including SLE, occurs when the immune system attacks a person’s own healthy tissues, causing pain, inflammation and tissue damage. Lupus most commonly affects the skin, joints, brain, lungs, kidneys and blood vessels. About 1.5 million Americans and 5 million people worldwide have a form of lupus, according to the Lupus Foundation of America.

Treatments for lupus aim to control symptoms, reduce immune system attack of tissues, and protect organs from damage. Only one targeted biologic agent has been approved for treating SLE, belimumab in 2011.

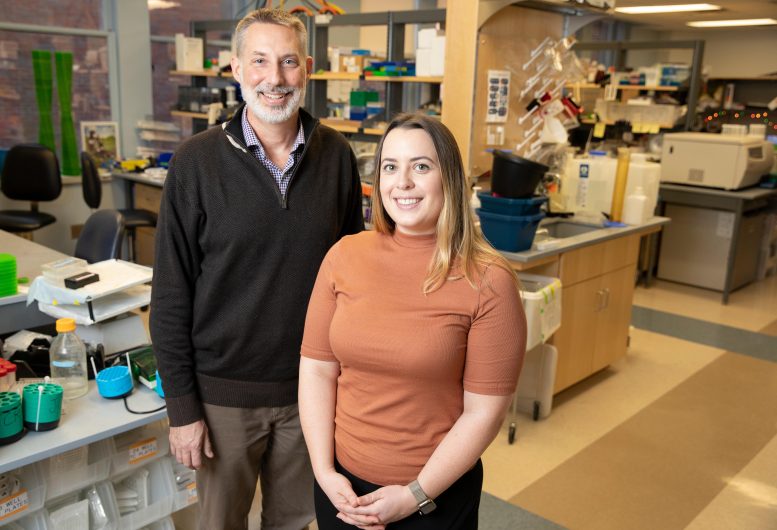

Jeffrey Rathmell, Ph.D., (left), and Kelsey Voss, Ph.D., led a multidisciplinary team that identified iron metabolism in T cells as a potential target for treating lupus. Credit: Vanderbilt University Medical Center

“It has been a real challenge to come up with new therapies for lupus,” said Jeffrey Rathmell, Ph.D., professor of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair in Immunobiology. “The patient population and the disease are heterogeneous, which makes it difficult to design and conduct clinical trials.”

Rathmell’s group has had a long-standing interest in lupus as part of a broader effort to understand the mechanisms of autoimmunity.

When postdoctoral fellow Kelsey Voss, Ph.D., began studying T cell metabolism in lupus, she noticed that iron appeared to be a “common denominator in many of the problems in T cells,” she said. She was also intrigued by the finding that T cells from patients with lupus have high iron levels, even though patients are often anemic.

“It was not clear why the T cells were high in iron, or what that meant,” said Voss, first author of the Science Immunology paper.

To explore T-cell iron metabolism in lupus, Voss and Rathmell drew on the expertise of other investigators at VUMC:

- Eric Skaar, Ph.D., and his team are experienced in the study of iron and other metals;

- Amy Major, Ph.D., and her group provided a mouse model of SLE; and

- Michelle Ormseth, MD, MSCI, and her team recruited patients with SLE to provide blood samples.

First, Voss used a CRISPR genome editing screen to evaluate iron-handling genes in T cells. She identified the transferrin receptor, which imports iron into cells, as critical for inflammatory T cells and inhibitory for anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells.

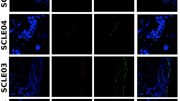

The researchers found that the transferrin receptor was more highly expressed on T cells from SLE-prone mice and T cells from patients with SLE, which caused the cells to accumulate too much iron.

“We see a lot of complications coming from that — the mitochondria don’t function properly, and other signaling pathways are altered,” Voss said.

An antibody that blocks the transferrin receptor reduced intracellular iron levels, inhibited inflammatory T cell activity, and enhanced regulatory T cell activity. Treatment of SLE-prone mice with the antibody reduced kidney and liver pathology and increased production of the anti-inflammatory factor, IL-10.

“It was really surprising and exciting to find different effects of the transferrin receptor in different types of T cells,” Voss said. “If you’re trying to target an autoimmune disease by affecting T cell function, you want to inhibit inflammatory T cells but not harm regulatory T cells. That’s exactly what targeting the transferrin receptor did.”

In T cells from patients with lupus, expression of the transferrin receptor correlated with disease severity, and blocking the receptor in vitro enhanced production of IL-10.

The researchers are interested in developing transferrin receptor antibodies that bind specifically to T cells, to avoid any potential off-target effects (the transferrin receptor mediates iron uptake in many cell types). They are also interested in studying the details of their unexpected discovery that blocking the transferrin receptor enhances regulatory T-cell activity.

Reference: “Elevated transferrin receptor impairs T cell metabolism and function in systemic lupus erythematosus” by Kelsey Voss, Allison E. Sewell, Evan S. Krystofiak, Katherine N. Gibson-Corley, Arissa C. Young, Jacob H. Basham, Ayaka Sugiura, Emily N. Arner, William N. Beavers, Dillon E. Kunkle, Megan E. Dickson, Gabriel A. Needle, Eric P. Skaar, W. Kimryn Rathmell, Michelle J. Ormseth, Amy S. Major and Jeffrey C. Rathmell, 13 January 2023, Science Immunology.

DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abq0178

The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, theNational Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, theNational Cancer Institute, and the Lupus Research Alliance.

Be the first to comment on "A New Potential Approach to Treating Lupus"