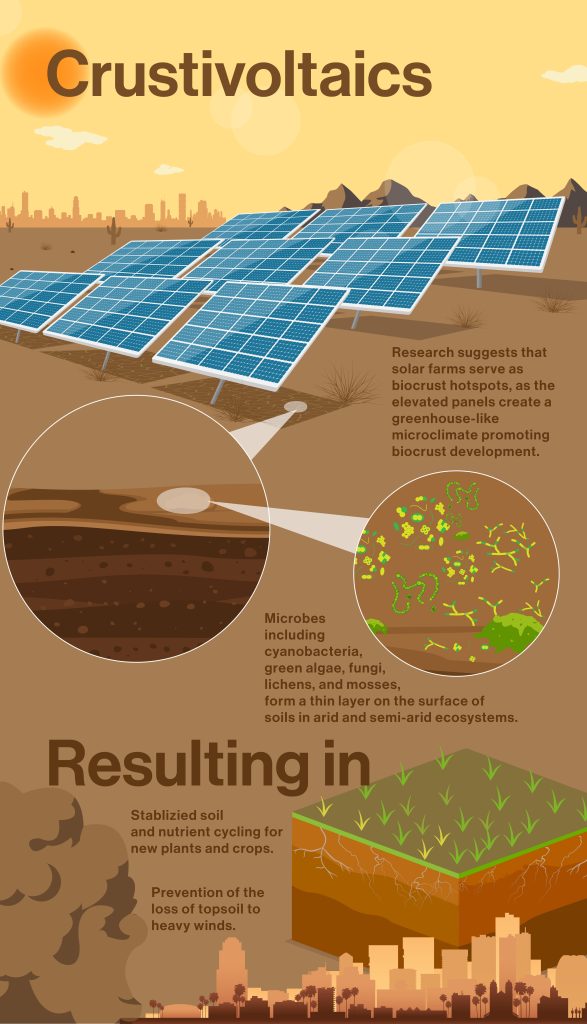

In a proof-of-concept study, ASU researchers adapted a suburban solar farm in the lower Sonoran Desert as an experimental breeding ground for biocrust. During the three-year study, photovoltaic panels promoted biocrust formation, doubling biocrust biomass and tripling biocrust cover compared with open areas with similar soil characteristics. Credit: Graphic by Shireen Dooling

Generating new soil crust in deserts using solar farms.

In the dry lands of the American Southwest, there is a hidden world beneath us. Biocrusts, also known as biological soil crusts, are made up of living organisms such as cyanobacteria, green algae, fungi, lichens, and mosses. These hardworking microorganisms form a delicate layer on top of the soil in arid and semi-arid cosystems

Biocrusts are essential to preserving soil wellness and ecosystem stability, yet they are facing challenges. Human actions such as farming, urbanization, and off-road driving can harm these biocrusts, leading to long-lasting harm to these delicate ecosystems. Climate change is also putting pressure on biocrusts, making it difficult for them to adjust to the intense heat and sunlight in arid regions like the Sonoran Desert.

Ferran Garcia-Pichel is a Regents’ Professor in the School of Life Science and the founding director of the Biodesign Center for Fundamental & Applied Microbiomics. Credit: The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University

Now, Ferran Garcia-Pichel and his student at Arizona State University propose an innovative approach to restoring healthy biocrusts. The idea is to use new and existing solar energy farms as nurseries for generating fresh biocrust.

Safely shielded from the sun beneath arrays of solar panels, like beachgoers under an umbrella, the biocrusts are sheltered from excessive heat and can flourish and develop. Ultimately, the newly generated biocrusts can then be used to replenish arid lands where such soils have been damaged or destroyed.

℞ for desert soil

In a proof-of-concept study, ASU researchers adapted a suburban solar farm in the lower Sonoran Desert as an experimental breeding ground for biocrust. During the three-year study, photovoltaic panels promoted biocrust formation, doubling biocrust biomass and tripling biocrust cover compared with open areas with similar soil characteristics.

When biocrusts were harvested, natural recovery was moderate, taking around 6-8 years to fully recuperate without intervention. However, when harvested areas were re-inoculated, the recovery was much faster, with biocrust cover reaching near-original levels within one year.

The researchers emphasize that the use of similar, but larger, solar farms could provide a low-cost, low-impact, and high-capacity method to regenerate biocrusts and expand soil restoration approaches to regional scales. They have dubbed their pioneering approach “crustivoltaics.”

Biocrusts are complex ecosystems researchers have only recently begun to explore. Among their many housekeeping functions, they act to stabilize soil by binding soil particles together, minimizing the loss of topsoil caused by wind and water. They contribute to nutrient cycling by fixing atmospheric nitrogen, a process where nitrogen gas is converted into ammonia, making it available to plants. Cyanobacteria, which are present in biocrusts, are the primary organisms responsible for this process. Credit: The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University

The study estimates that the use of the three largest solar farms in Maricopa County, Arizona as biocrust nurseries could empower a small-scale enterprise to rejuvenate all idle agricultural lands within the county, spanning more than 70,000 hectares, in under five years. Among many environmental benefits, this restoration effort has the potential to significantly decrease airborne dust presently impacting the Phoenix Metropolitan region.

“This technology can be a game changer for arid soil restoration,” Garcia-Pichel says. “For the first time reaching regional scales at our fingertips, and we could not be more excited. To boot, crustivoltaics represents a win-win approach for conservation of arid lands and for the energy industry alike.”

Garcia-Pichel is a Regents’ Professor in the School of Life Science and the founding director of the Biodesign Center for Fundamental & Applied Microbiomics. The center amalgamates researchers that study assemblages of microbes (or microbiomes) acting in unison in various settings, from humans to animals and plants, to oceans and deserts. Garcia-Pichel’s lab has specialized in the study and applications of desert soil microbiomes.

The group’s findings appear in the current issue of the journal Nature Sustainability, in a publication co-lead by graduate student Ana “Meches” Heredia-Velásquez, and former graduate student Dr. Ana Giraldo-Silva, now a professor at the Public University of Navarre in Spain. A separate briefing of this contribution appears concurrently in Nature.

Living matrix

Biocrusts are complex ecosystems researchers have only recently begun to explore. Among their many housekeeping functions, they act to stabilize soil by binding soil particles together, minimizing the loss of topsoil caused by wind and water. They contribute to nutrient cycling by fixing atmospheric nitrogen, a process where nitrogen gas is converted into ammonia, making it available to plants. Cyanobacteria, which are present in biocrusts, are the primary organisms responsible for this process.

Photosynthetic activities within biocrusts play a role in carbon storage by fixing atmospheric carbon dioxide. This process can help mitigate some of the effects of climate change by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Biocrusts also increase the soil’s water-retaining capacity, allowing more water to infiltrate the soil and reducing runoff. This helps to improve water availability for plants and other organisms in arid ecosystems.

Finally, biocrusts support a diverse community of microorganisms that contribute to overall ecosystem biodiversity and resilience.

Drylands, which make up approximately 41% of the Earth’s continental area, are experiencing severe degradation due to human activities and climate change. The communities of microorganisms on soil surfaces are vital to protect and fertilize these soils and are essential for dryland sustainability. However, current biocrust restoration methods involve high effort and low capacity, limiting their application to small areas. Existing methods have struggled to replenish more than a few hundred square meters of land.

Solar solutions

The research suggests that solar farms serve as biocrust hotspots, as the elevated photovoltaic panels create a greenhouse-like microclimate promoting biocrust development. Although crustivoltaics is a slower and weather-dependent method compared to greenhouse-sized biocrust nurseries, it has many advantages. The technique requires fewer resources, minimal management, and no upfront investment. Indeed, the use of crustivoltaics is 10,000 times more cost-effective than current methods, according to the research findings.

The next steps will involve implementing crustivoltaics at regional scales through the cooperation of scientists, collaborative agencies, land users, and managers. The use of the technique can provide incentives to solar farm operators, including reduced dust formation on solar panels and increased revenue from carbon credits.

The crustivoltaic approach has the potential to offer a dual-use solution for both solar power generation and biocrust restoration on a large scale, while also providing socioeconomic benefits. This method could play a significant role in the restoration and sustainability of dryland ecosystems.

Reference: “Dual use of solar power plants as biocrust nurseries for large-scale arid soil restoration” by Ana Mercedes Heredia-Velásquez, Ana Giraldo-Silva, Corey Nelson, Julie Bethany, Patrick Kut, Luis González-de-Salceda and Ferran Garcia-Pichel, 20 April 2023, Nature Sustainability.

DOI: 10.1038/s41893-023-01106-8

Be the first to comment on "“Crustivoltaics” – A New Way To Replace Biocrusts Damaged by Humans"