Artistic reconstruction of a group of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis swimming in the Cambrian sea. Credit: Reconstruction by Christian McCall. © Christian McCall

505-million-year-old swimming jellyfish from the Burgess Shale highlights diversity in Cambrian ecosystem.

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) has announced the discovery of the oldest known swimming jellyfish in the fossil record, the newly named Burgessomedusa phasmiformis. The discovery was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

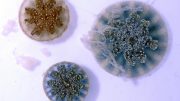

Jellyfish are part of the medusozoans, a group of animals producing medusae, and includes present-day creatures like box jellies, hydroids, stalked jellyfish, and true jellyfish. Medusozoans are part of the ancient animal group called Cnidaria, which also contains corals and sea anemones.Burgessomedusa is a definitive indication that large, swimming jellyfish with a traditional bell-shaped body had already evolved over 500 million years ago.

Burgessomedusa Fossils and Their Features

Burgessomedusa fossils are exceptionally well preserved at the Burgess Shale considering jellyfish are roughly 95% composed of water. ROM holds close to two hundred specimens from which remarkable details of internal anatomy and tentacles can be observed, with some specimens reaching more than 20 centimeters in length. These details enable classifying Burgessomedusa as a medusozoan. By comparison with modern jellyfish, Burgessomedusa would also have been capable of free-swimming and the presence of tentacles would have enabled capturing sizeable prey.

Slab showing one large and one small (rotated 180 degrees) bell-shaped specimens with preservation of tentacles. ROMIP 65789. Credit: Photo by Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

“Although jellyfish and their relatives are thought to be one of the earliest animal groups to have evolved, they have been remarkably hard to pin down in the Cambrian fossil record. This discovery leaves no doubt they were swimming about at that time,” said co-author Joe Moysiuk, a Ph.D. candidate in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto, who is based at ROM.

The Significance of the Burgessomedusa Discovery

This study, identifying Burgessomedusa, is based on fossil specimens discovered at the Burgess Shale and mostly found in the late 1980s and 1990s under former ROM Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology Desmond Collins. They show that the Cambrian food chain was far more complex than previously thought, and that predation was not limited to large swimming arthropods like Anomalocaris (see field image showing Burgessomedusa and Anomalocaris preserved on the same rock surface).

Field images of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis jellyfish specimens (middle right ROMIP 65789 – see close up images) and of the top arthropod predator Anomalocaris canadensis preserved on the same rock surface. Hammer for scale. Credit: Photo by Desmond Collins. © Royal Ontario Museum

“Finding such incredibly delicate animals preserved in rock layers on top of these mountains is such a wonderous discovery. Burgessomedusa adds to the complexity of Cambrian foodwebs, and like Anomalocaris which lived in the same environment, these jellyfish were efficient swimming predators,” said co-author, Dr. Jean-Bernard Caron, ROM’s Richard Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Palaeontology. “This adds yet another remarkable lineage of animals that the Burgess Shale has preserved chronicling the evolution of life on Earth.”

Detail of previous image showing Burgessomedusa phasmiformis jellyfish specimens (middle right ROMIP 65789) and of the top arthropod predator Anomalocaris canadensis. Credit: Photo by Desmond Collins. © Royal Ontario Museum

The Elusive Origins of the Medusa Form

Cnidarians have complex life cycles with one or two body forms, a vase-shaped body, called a polyp, and in medusozoans, a bell or saucer-shaped body, called a medusa or jellyfish, which can be free-swimming or not. While fossilized polyps are known in ca. 560-million-year-old rocks, the origin of the free-swimming medusa or jellyfish is not well understood.

Fossils of any type of jellyfish are extremely rare. As a consequence, their evolutionary history is based on microscopic fossilized larval stages and the results of molecular studies from living species (modeling of divergence times of DNA sequences).

ROM Burgess Shale fieldwork site in Yoho National Park, Raymond Quarry, in 1992. Credit: Photo by Desmond Collins. © Royal Ontario Museum

Though some fossils of comb-jellies have also been found at the Burgess Shale and in other Cambrian deposits, and may superficially resemble medusozoan jellyfish from the phylum Cnidaria, comb-jellies are actually from a quite separate phylum of animals called Ctenophora. Previous reports of Cambrian swimming jellyfish are reinterpreted as ctenophores.

Reference: “A macroscopic free-swimming medusa from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale” by Justin Moon, Jean-Bernard Caron and Joseph Moysiuk, 2 August 2023, Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.

DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2022.2490

Funding: NSERC Discovery Grant

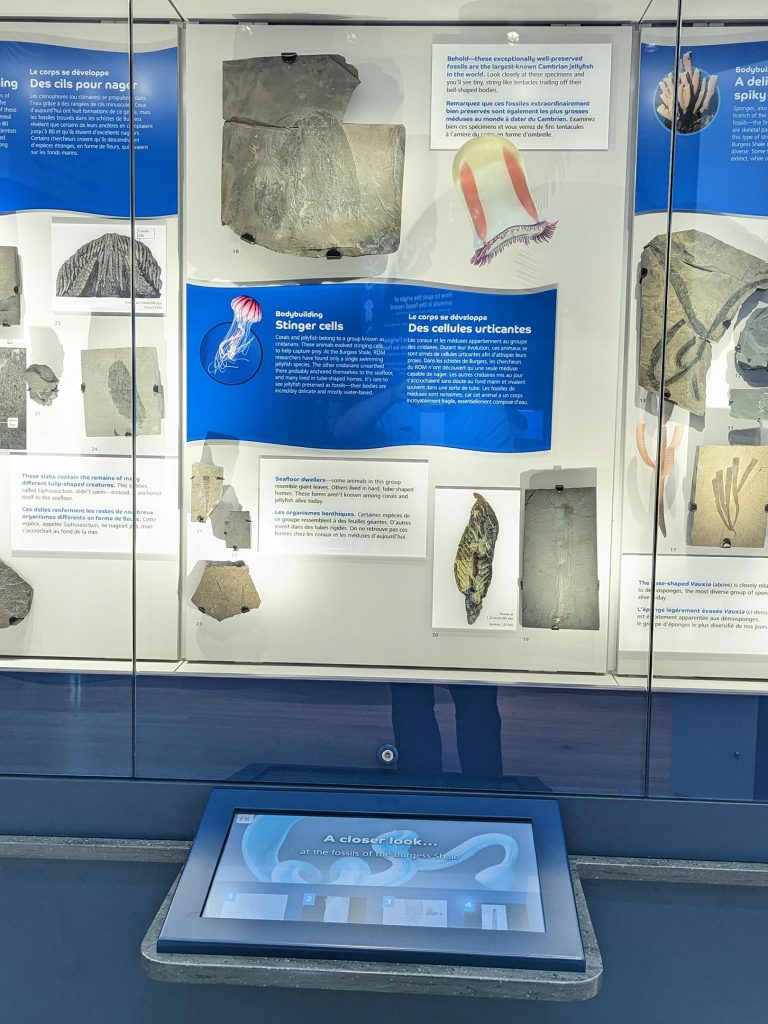

Display of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis in the Burgess Shale section of ROM Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life. Credit: Photo by David McKay. © Royal Ontario Museum

The Burgess Shale fossil sites are located within Yoho and Kootenay National Parks and are managed by Parks Canada. Parks Canada is proud to work with leading scientific researchers to expand knowledge and understanding of this key period of Earth history and to share these sites with the world through award-winning guided hikes. The Burgess Shale was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 due to its outstanding universal value and is now part of the larger Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.

Visitors to ROM can see fossils of Burgessomedusa phasmiformis on display in the Burgess Shale section of the recently opened Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life.

We have soft tissue of a triceratop, soft tissue, the dinosaurs are not millions of years old. Soft tissue is the evidence.

Also we don’t see any animal evolving into a dinosaur or a dinosaur devolving into anything else, they went extinct.