Researchers have discovered evidence of Down Syndrome and Edwards Syndrome in ancient DNA, tracing back to between 2,500 and 5,000 years ago, revealing these individuals received care and were appreciated within their societies. They found burials with grave goods and within settlements, suggesting a societal acceptance, and plan to expand research on how ancient societies treated individuals with such conditions.

Burial practices indicate that individuals with Down Syndrome and Edwards Syndrome were recognized as members of their communities

For many years, scientists at MPI-EVA have dedicated their efforts to gathering and examining ancient human DNA from individuals who lived during the past tens of thousands of years. Analyzing these data has allowed the researchers to trace the movement and mixing of people, and even to uncover ancient pathogens that affected their lives. However, a systematic study of uncommon genetic conditions had not been attempted. One of those uncommon conditions, known as Down Syndrome, affects nowadays around one in 1,000 births.

To their surprise, Adam “Ben” Rohrlach and colleagues identified six individuals with an unusually high number of DNA sequences from Chromosome 21 that could only be explained by an additional copy of Chromosome 21. One case from a church graveyard in Finland was dated to the 17th to 18th century.

Remains of individual “CRU001”, who the researchers discovered had Down syndrome. The remains were found at a site in Spain dating to the Iron Age. Credit: Photograph from the Government of Navarre and J.L. Larrion.

The remaining five individuals were much older: dating to between 5,000 and 2,500 years before the present, they were found at Bronze Age sites in Greece and Bulgaria, and Iron Age sites in Spain. In all cases, the researchers were able to obtain a wealth of additional information about the remains and the burials.

Burials within settlements and with grave goods

While individuals with Down Syndrome can live a long life today, often with the help of modern medicine, this was not the case in the past. Indeed, age estimates from skeletal remains showed that all six individuals died at a very young age, with only one child reaching around one year of age. The five prehistoric burials were all located within settlements and in some cases accompanied by special items such as colored bead necklaces, bronze rings, or sea-shells. “These burials seem to show us that these individuals were cared for and appreciated as part of their ancient societies,” says Rohrlach, the lead author of the study.

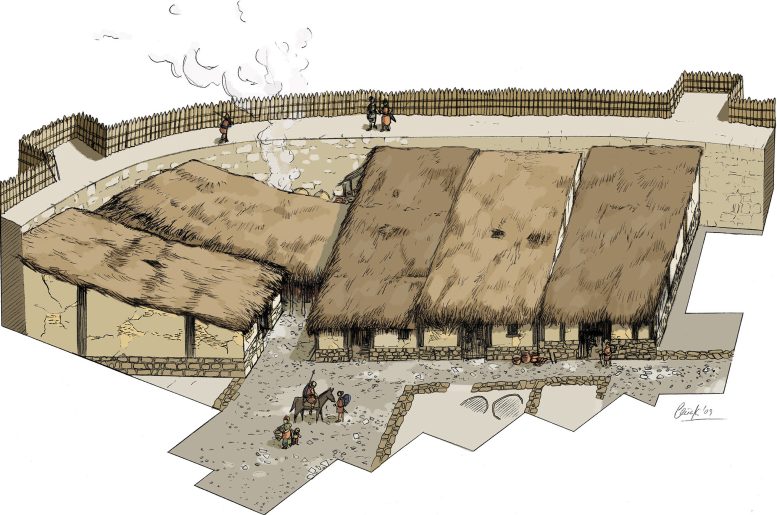

Reconstruction of the Early Iron Age settlement of Las Eretas, Navarra. Credit: Iñaki Diéguez/Javier Armendáriz, Museo Las Eretas, Navarra

Although the study was aimed at finding cases of Down Syndrome, the researchers also discovered an individual with a different condition. Among the approximately 10,000 tested DNA samples, one individual had an unexpectedly high fraction of ancient DNA sequences from Chromosome 18 that showed that she carried three copies of this chromosome. Three copies of Chromosome 18 are known to cause Edwards Syndrome, a condition associated with more severe health issues than Down syndrome. With an incidence of less than one case in 3,000 births, Edwards Syndrome also occurs much less often than Down Syndrome.

This find, too, was made at one of the Spanish Iron Age sites, leaving the researchers with a mystery to solve. “At the moment, we cannot say why we find so many cases at these sites,” says Roberto Risch, an archaeologist of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona working on intramural funerary rites, “but we know that they belonged to the few children who received the privilege to be buried inside the houses after death. This already is a hint that they were perceived as special babies.”

Aerial view of the Early Iron Age settlement of Alto de la Cruz, Navarra, during the 1989 excavation campaign. Credit: Servicio Patrimonio Histórico Gobierno de Navarra

As the number of DNA samples from ancient individuals continues to increase, the authors plan to further expand their research in the future. “What we would like to learn is how ancient societies reacted to individuals that may have needed a helping hand or were simply a bit different,” says Kay Prüfer, who coordinated the sequence analysis.

Reference: “Cases of trisomy 21 and trisomy 18 among historic and prehistoric individuals discovered from ancient DNA” by Adam Benjamin Rohrlach, Maïté Rivollat, Patxuka de-Miguel-Ibáñez, Ulla Moilanen, Anne-Mari Liira, João C. Teixeira, Xavier Roca-Rada, Javier Armendáriz-Martija, Kamen Boyadzhiev, Yavor Boyadzhiev, Bastien Llamas, Anthi Tiliakou, Angela Mötsch, Jonathan Tuke, Eleni-Anna Prevedorou, Naya Polychronakou-Sgouritsa, Jane Buikstra, Päivi Onkamo, Philipp W. Stockhammer, Henrike O. Heyne, Johannes R. Lemke, Roberto Risch, Stephan Schiffels, Johannes Krause, Wolfgang Haak and Kay Prüfer, 20 February 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-45438-1

The study was funded by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, the H2020 European Research Council, and the Australian Research Council.

Be the first to comment on "Time-Traveling Genes: Ancient DNA Reveals Down Syndrome in Past Human Societies"