Researchers have uncovered significant diversity in the TAS1R gene family, responsible for taste perception in vertebrates. This discovery, derived from a genome-wide survey, sheds light on the evolutionary history of taste receptors and has potential applications in developing specialized foods for various animal species.

A genome-wide survey has uncovered substantial diversity in the evolution of taste receptors across vertebrates.

Taste perception is a critical sense, playing a key role in distinguishing nourishing foods from potential toxins. This is exemplified in our preference for sweet and savory flavors, which aligns with the body’s requirements for carbohydrates and proteins. Due to its evolutionary significance, scientists globally are exploring the origins and development of taste receptors through time. Understanding these aspects of feeding behavior in various organisms contributes to a broader understanding of life’s history on our planet.

One of the important tastes in our taste palette is umami, or the savory taste, which is associated with proteins that form a vital part of the diets of many organisms. The taste receptor type 1 (T1R) detects sweet and umami tastes among mammals. This taste receptor is encoded by the TAS1R, a family of genes, including TAS1R1, TAS1R2, and TAS1R3, and comes from a common ancestor of bony vertebrates. However, this gene pattern is not observed in coelacanth and cartilaginous fishes, where ‘taxonomically unplaced’ TAS1R genes have been identified, suggesting an incomplete understanding of the evolutionary history of taste receptors.

Discovery of New TAS1R Groups

Now, however, a research team led by Associate Professor Hidenori Nishihara from Kindai University and Professor Yoshiro Ishimaru from Meiji University, Japan, have identified five new, previously undiscovered groups within the TAS1R family. This discovery is a result of a genome-wide survey of jawed vertebrates including all major fish groups.

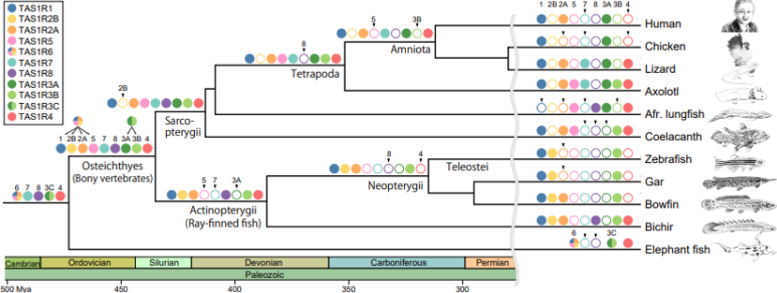

A new study led by researchers from Kindai University identified five new groups of umami and sweet taste receptors within the TAS1R family (TAS1R 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) and also diversity in TAS1R2 and TAS1R3 genes. Credit: Hidenori Nishihara from Kindai University

The study was published in Nature Ecology & Evolution on December 13, 2023 and included the contributions of Senior Assistant Professor Yasuka Toda from Meiji University, Professor Masataka Okabe from The Jikei University School of Medicine, Professor Shigehiro Kuraku from the National Institute of Genetics, and Project Associate Professor Shinji Okada from The University of Tokyo.

“Our study revealed that as compared to most modern vertebrates, the vertebrate ancestor possessed more T1Rs. These findings challenge the paradigm that only three T1R family members have been retained during evolution,” says Prof. Nishihara.

The novel taste receptor genes, named TAS1R4, TAS1R5, TAS1R6, TAS1R7, and TAS1R8 by the researchers, were categorized based on their distribution among species with a common ancestor. The researchers found TAS1R4 genes to be present in lizards, axolotl, lungfishes, coelacanth, bichir, and cartilaginous fishes, but absent in mammals, birds, crocodilians, turtles, and teleost fishes.

The color key indicates the names of the various T1R members. Filled, colored circles on the branches indicate the presence of the TAS1R members, whereas open circles indicate their absence. Arrowheads above open circles indicate that the TAS1R member was lost at the branch. Credit: Hidenori Nishihara from Kindai University

Moreover, axolotl, lungfishes, and coelacanth were found to have TAS1R5. The researchers observed a close evolutionary relationship between TAS1R5, TAS1R1, and TAS1R2, indicating a shared ancestry between these genes. The cartilaginous fishes possess TAS1R6 exclusively. Notably, the researchers found that TAS1R6 evolved from the same ancestral gene that led to TAS1R1, TAS1R2, and TAS1R5 genes. While axolotl and lizards possess TAS1R7, bichir and lungfishes possess TAS1R8. The researchers determined that these two genes originated in the common ancestor of jawed vertebrates.

Diversity and Duplication in TAS1R Genes

In addition to these new genes, the study revealed diversity in the existing TAS1R genes. For instance, they found that TAS1R3 of bony vertebrates could be divided into TAS1R3A and TAS1R3B. TAS1R3A was present in tetrapods and lungfishes, while TAS1R3B was identified in amphibians, lungfishes, coelacanths, and ray-finned fishes. Additionally, the genome survey found TAS1R2 to have diversified into two distinct groups (TAS1R2A and TAS1R2B), challenging the conventional idea that TAS1R2 forms a single gene group.

“We found that the TAS1R phylogenetic tree comprises of a total of 11 TAS1R clades, revealing an unexpected gene diversity,” adds Prof. Nishihara.

The findings also suggest that the first TAS1R gene appeared in jawed vertebrates around 615–473 million years ago. The gene then underwent several duplications to produce nine taste receptor genes (TAS1R1,2A, 2B, 3A, 3B, 4, 5, 7, and 8) in the common ancestor of bony vertebrates. Over time, some of these genes were lost in different lineages, with mammals and teleosts retaining only three TAS1Rs (TAS1R1, TAS1R2A, and TAS1R3A in mammals).

In addition to shedding light on the evolutionary history, the findings also have practical applications. Explaining these to us, Prof. Nishihara says, “These findings make it easier for us to deduce the taste preferences of diverse vertebrates. This, in turn, can have potential applications such as the development of pet foods and attractants tailored to the preferences of fish, amphibians, and reptiles.”

Be the first to comment on "Why Do Humans Like Sweet Things? Scientists Unravel Evolutionary Origins of Taste Preferences"